Several of the signatories of the petition to Cardinal Oswald Gracias of Mumbai, India, stand together in front of a statue of Pope John Paul II near Mumbai's Holy Name Cathedral March 8. (Courtesy of Astrid Lobo Gajiwala)

Indian Cardinal Oswald Gracias had to know when he declared that he had undergone a conversion and was now an advocate for women seeking leadership roles in the global church that those words would not be the last on the subject.

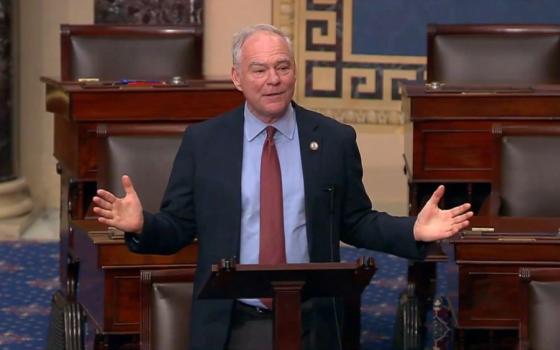

Cardinal Oswald Gracias of Mumbai, India, at the Vatican in 2014 (CNS/Paul Haring)

Gracias made his comments during a Feb. 21 interview with NCR's Vatican correspondent, Joshua McElwee. Gracias is not just any cardinal. The archbishop of Mumbai, he is also president of the Indian bishops' conference and a member of Pope Francis' Council of Cardinals.

One might reasonably conclude that his conversion to the cause is one more step in the often painfully slow walk toward the inevitability that women in the Catholic world may at some point be restored to the status appropriate to those who were first to witness the empty tomb.

But the daunting question — how to get from here to there? — hangs over the best intentions.

And there is much to overcome. After all, from the imagination of an all-male, celibate, secretive culture have come such ideas about women as malformed males, seductresses, the equivalent of fertile containers, walking incubators, the frail and witless inferior sex. Women were once defined by an ancient male clerical motto: "aut maritus, aut murus" (either a husband or a cloister wall).

More recent attempts at understanding have found male celibates swooning over the splendors of virginity, expounding tortuous theories about "feminine genius," and mansplaining, in the sincerest tones they can muster, how ordination has nothing to do, really, with power, but everything to do with service.

The reality, easily observable, is that most of the service in the church, especially in the form of ministry and teaching, is done by women. The power to decide resides almost exclusively (rare exceptions exist) with ordained men.

Lay leaders in the church, the majority of whom are women, have taken on abundant responsibility yet have little authority to decide how to exercise that responsibility.

Advertisement

Gracias was speaking primarily about giving recognition to women who have taken on the bulk of leadership in parishes and dioceses. He admitted that the church hierarchy has a bias against giving women leadership roles in the church and said he and others must "shed this prejudice."

"I am now an advocate for women's rights in the church," he said. "I empathize with why women are asking for greater rights."

It didn't take long for women in India to take up the cardinal and offer to help him in his new cause. He was delivered a three-page memorandum signed by about 150 Catholic women in India, a church that in 2010 passed a gender policy, thought to be the first of its kind in the global church, that "rejects all types of discrimination against women as being contrary to God's intent and purpose."

The women's memorandum asks for "changes in the policies, practices and structures of the Church so that women can participate fully in … leadership."

The heavy lift, of course, will be finding like-minded advocates in the all-male clerical culture who will acknowledge that "discrimination" is the term that describes treatment of women in the church.

It is the fundamental premise of the memo: "Women continue to be discriminated against by keeping them out of decision-making bodies of the Church, which are controlled by clerics. Women have no say in the policy-making that shapes the liturgy, worship, theology and practices of the church, including those that affect their own lives."

That is as clear a description of the essential disagreement as one might find. And the ages-old conundrum remains: How do women convince a clerical culture whose members claim that their ordination, available only to men, grants them a status apart from other humans, to enact reforms that would diminish that status and end exclusivity?

Gracias has set himself a formidable task.