A bishop's voting device, prayer book and ring are pictured during a Nov. 16 session of the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

At their annual fall meeting in Baltimore that ended Nov. 18, the U.S. Catholic bishops showed they are still unable to reach consensus on the directions they should give to American Catholics on politics. This lack of consensus has been exposed every four years since 2007, the last time the bishops were able to issue a completely new version of "Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship," their quadrennial teaching document on "the political responsibility of Catholics."

In the years since, the bishops have either amended the 2007 text or simply added an introductory letter. At the fall meeting, the bishops decided to leave the next version, due out in 2023, unchanged except for the addition of some supplemental materials such as videos and bulletin inserts.

The fact is, few people read "Faithful Citizenship," so the bishops have looked for other ways to communicate their message. The inserts, to be offered to churches across the country to add to their parish's Sunday bulletins, have been one solution. This year, however, the bishops determined to provide several bulletin inserts on various topics. This could inadvertently lead to pastors picking and choosing which ones they will distribute. One might include a bulletin insert on abortion, while another might use one on economic justice.

Meanwhile, the bishops plan to begin the process of re-examining "Faithful Citizenship" immediately after the 2024 election so that a new document can be prepared for approval at their November 2027 meeting in time for the 2028 election.

Supporters of this decision said they did not want to simply amend the 2007 document again but also realized the conference could not draft and approve a new document in time for approval next November. By kicking the can way down the road, the bishops can avoid a bitter political fight. A good number of the bishops who voted to wait knew that they will be retired by 2027.

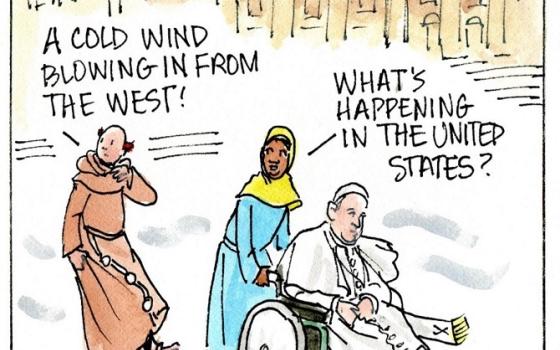

Although progressive bishops want a new document that incorporates the teachings of Pope Francis, they did not fight very hard for it. They know they do not have the votes to get a document to their liking.

In the Nov. 15 election for secretary of the USCCB, pro-Francis Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey, lost to conservative Archbishop Paul S. Coakley of Oklahoma City by a vote of 104 to 130, which shows how the conference is divided. The bishops even elected as their president Archbishop Timothy P. Broglio, who did not get along with Francis when he was archbishop of Buenos Aires and Broglio was an aide to Cardinal Angelo Sodano, the Vatican's secretary of state.

The progressives hope that new bishops appointed by Francis will eventually turn the tide in the future.

Conservatives, on the other hand, are happy with the document and introductory letter approved in 2019 that made abortion the "preeminent priority" of the conference. Anything that would threaten that decision would be anathema to conservatives. As a result, they were happy to have the conference do little or nothing. They also know that Francis will probably be gone by 2027.

Writing a document on politics has never been easy for the bishops. As my 1992 book, A Flock of Shepherds, describes, the conference's first document on political responsibility was approved by the bishops in 1976 when Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago was president of the then-National Conference of Catholic Bishops, later renamed the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Even then, the bishops had been accused of talking only about abortion, and the statement was an attempt to show their concern about other issues. By issuing a new document every four years before presidential elections, the thinking went, the bishops could reflect on current political issues from the perspective of Catholic social teaching. It would encourage Catholics to vote but not tell them how to vote.

While the bishops had disagreements over issues and their priorities, the conference often successfully worked through these disagreements and reached consensus on the documents, which required a two-thirds majority vote for approval.

But from the very beginning, some bishops wanted to make abortion the most important issue for Catholics, while others preferred to list the issues without prioritizing them.

Bernardin spoke of a "consistent ethic of life," which some referred to as the "seamless garment" approach. According to this approach, Catholics should be concerned about life from conception to natural death or from "womb to tomb," as some wags described it.

The Bernardin faction thought it was a political and pastoral mistake to say that abortion was more important than any other issue, including nuclear war, economic justice, racial equality and care for the poor. They also recognized that most women get abortions for economic reasons and that government welfare programs reduce the number of abortions.

Advertisement

Making abortion the priority would imply that the other issues could be set aside until after abortion was dealt with. Many feared that the conference would be seen as a single-issue lobby. Politically, saying that abortion was the most important issue would be equivalent to saying, "Vote for Republicans."

In the 1976 statement, the solution was to list the issues in alphabetical order, which placed abortion first without saying it was more important than the other issues.

Under the papacy of John Paul II, the bishops supporting the Bernardin approach were gradually replaced by bishops wanting to take a tougher stance on abortion.

Finally, in 2019, they added an introductory letter to the statement that said, "The threat of abortion remains our preeminent priority because it directly attacks life itself, because it takes place within the sanctuary of the family, and because of the number of lives it destroys." At the meeting, the president of the conference, Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, said that global warming was an important issue but not urgent like abortion.

While "Faithful Citizenship" is a valuable document, the political world has changed significantly since the last time the bishops discussed it. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision legalizing abortion.

The decision caused a serious backlash in the 2022 midterm election, with Democrats doing much better than anticipated. In addition, prolife groups suffered defeat on all the state referenda dealing with abortion.

There was nothing said at the bishops' meeting indicating that they know how to deal with this post-Dobbs, post-election reality other than to say, "more of the same."

Meanwhile, there are major new political issues, such as the rise of Christian nationalism, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and threats to democracy, as exemplified by Trump's refusal to accept the results of the 2020 election and the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection. Other issues have gotten worse, such as global warming, race relations, economic inequality and the plight of migrants and refugees.

It is doubtful that whatever the bishops say will have much effect on the 2024 election. The bishops have little credibility, and Catholic voters will make up their own minds, but it is sad that the church does not have a prophetic word to say when our country and the world are in crisis.