Dominican Sister Donna Markham, president and CEO of Catholic Charities USA, speaks during a Nov. 15, 2022, session of the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

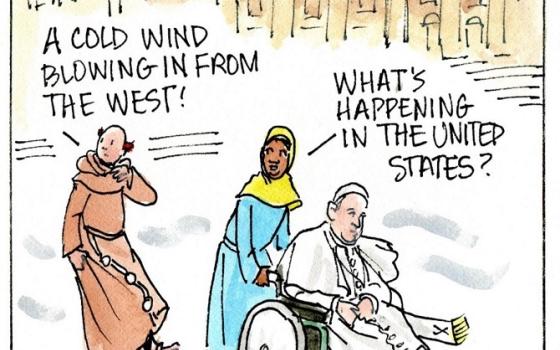

At the recent U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops fall meeting in Baltimore (Nov. 14-17), pro-Francis bishops lost for the most part to anti-Francis bishops in elections to the conference's top offices, sending a loud message to Rome and the rest of the English-speaking world.

The church's right wing is celebrating the new USCCB president, Archbishop Timothy Broglio, a career Vatican diplomat who has headed the Archdiocese for the Military Services since 2007. From 1990 to 2001, Broglio was an influential aide to Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Angelo Sodano. It was during Broglio's time in Rome that the cardinal blocked investigations of notorious sexual abuser Fr. Marcial Maciel Delgado.

Broglio blames homosexuality for the abuse crisis and has supported religious objections to COVID-19 vaccines. While transparency is a hallmark of the Synod on Synodality, the Archdiocese for the Military Services is among the minority of U.S. dioceses that does not post a synod synthesis.

Though, in a nod to synodality, as the bishops sat at round tables in the Baltimore Marriott ballroom, all the elected officers are on the right side of the aisle. One after another, more moderate candidates fell to the culture warriors.

During the meeting, the bishops heard a presentation about the multimillion dollar plans for the National Eucharistic Congress, scheduled for Indianapolis in July 2024. They spoke about liturgy and approved causes for canonization. They decided not to rewrite their outdated voters guide.

What is most telling is that the time the bishops spent on these issues far exceeded the time spent on what the church is called to do: minister to the poor, to the hungry, to the thirsty, to the homeless, the sick, the imprisoned and the dead.

Advertisement

Yes, the bishops discussed publishing a book to aid lay persons who minister to the sick. Yes, an abuse survivor and Newark's Cardinal Joseph Tobin (who lost election as conference secretary) presented strong statements toward the end of one day's sessions. Yes, there was discussion about the synod, whose next phase will be conducted via Zoom among representatives chosen only by the bishops. The chair of the migration committee reported that, working with other agencies, the bishops' Migration and Refugee Services helped to resettle some 1,300 Afghans.

Yet the clearest statement about dedication to Christian charity came from Dominican Sister Donna Markham, retiring president and CEO of Catholic Charities USA, the giant umbrella over 167 agencies and some 3,400 locations serving more than 15 million persons annually. Markham detailed the ways her agency directed what she termed "the Catholic Church's response in this country to people who reside along the margins of our society ... this is where our church puts the Gospel into action."

Markham said the largest percentage of Catholic Charities' budget comes from outside sources: Only 1% comes from the annual USCCB collection, another 5% from member agency dues.

The fact that a woman gave the strongest example of what the church is and needs to do is instructive of the quagmire the bishops find themselves in.

Twenty years ago, the body approved the "Dallas Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People." At the time, at least one bishop, Fabian Bruskowitz of Lincoln, Nebraska, refused to implement the strictures. The USCCB did not hold him accountable. Since then, state after state has produced staggering statistics documenting a pattern of sex abuse by its clerics.

To be sure, safeguarding is important, but it is only one part of the equation. Until seminaries put human formation at the top of the list, they will continue to produce clerics--not all of them, but many of them--who preach politics rather than the Gospel and who are lawgivers rather than agents of mercy.

That is why Catholics and others are left wondering what the USCCB is all about. That is why so many Catholics have simply left.