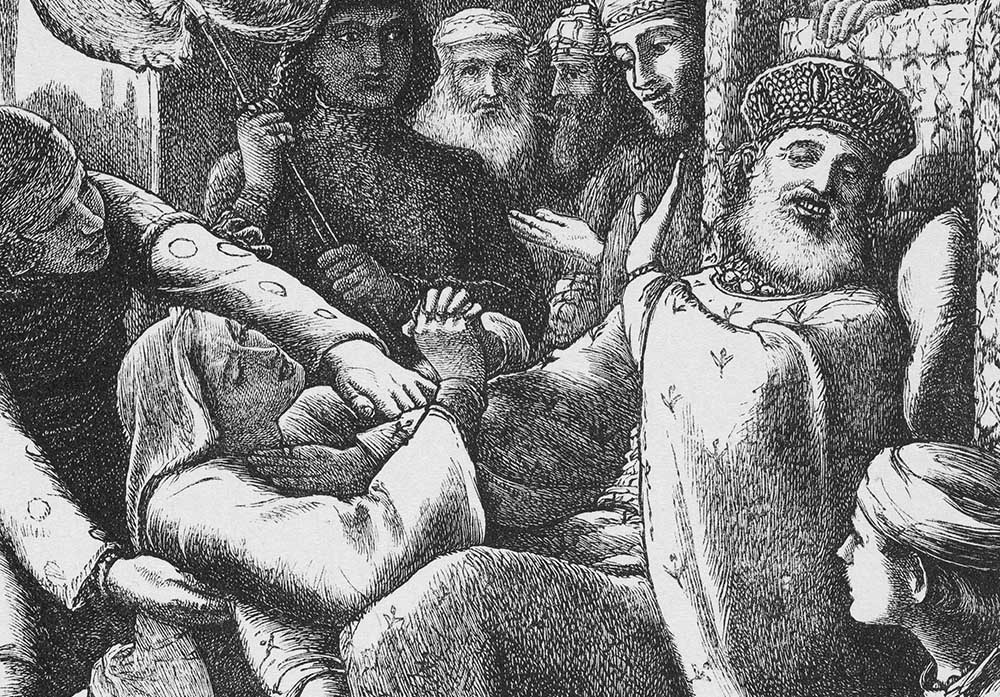

Detail from "The Unjust Judge and the Importunate Widow" (1864), created by John Everett Millais, engraved and printed by the Dalziel Brothers (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

John Everett Millais' "The Unjust Judge and the Importunate Widow" is almost as intriguing as Jesus' parable on which the image is based: A persistent widow unrelentingly demands justice from an unjust judge who does not "fear God" or respect other human beings. The judge refuses the widow's repeated petitions but eventually grants her justice so she will not "wear him out" (Luke 18:2-5).

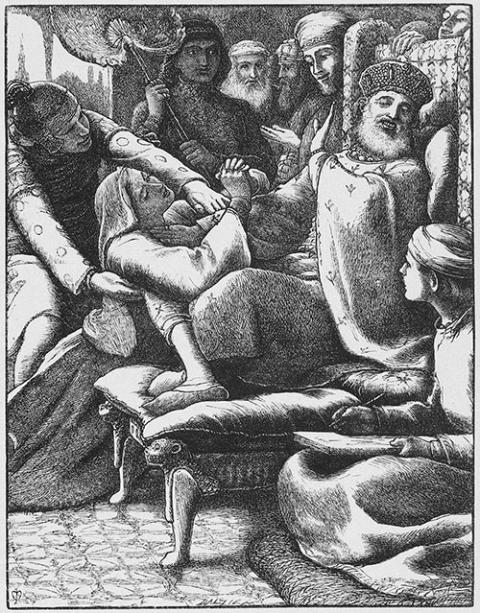

In Millais' image, the judge sits with his legs crossed on a throne-like cushioned chair. He wears fine clothes, pointed slippers and a bejeweled hat. His right hand pushes the woman away, and his left hand is upraised — in effect telling her to stop, that he has heard enough and that his answer is no. His head turns from her, and his smiling face reflects a haughty, superior disdain for her pleas.

The woman kneels by his feet on the right side of his chair, her hands clasped in supplication, and her right arm reaches over the judge's right knee. Her eyes are steadily focused on the unjust judge, perhaps a hint that she will persevere, no matter how much he ignores her.

The faces are what stand out the most in the image, especially the mocking, contemptuous dismissal of the widow reflected in the judge's face, and the desperate yet insistent face of the woman for whom the judge is her last recourse. There is no sign yet that the judge will relent, but the widow will not be deterred, even with the guard grabbing her with both hands and trying to drag her away. She kneels, the sole woman in a room filled with men, which accentuates her isolation and apparent powerlessness.

In the foreground, a secretary sits on a cushion on the floor next to the judge's chair. He holds a tablet on his lap and a writing instrument in his right hand. He looks up at the woman expectantly and, perhaps, sympathetically — an emotion lacking from most of the others in the image — waiting to see what, if anything, will happen.

Just to the right of the guard is a servant holding a fan, another sign that, unlike the woman, the powerful judge has every comfort available to him. The servant looks at the judge and he shares the judge's amusement at the woman's predicament, as does the man just beside him, who also raises his hand, seemingly to direct the woman to leave the judge's presence. Similar amusement may be found in the face of the young man who awkwardly peers over the top of the judge's chair.

Advertisement

Two men, however, stand in the background, both with full, long beards and neither with a trace of amusement on their faces. One man stands in profile, but the other looks directly at the viewers, in effect challenging, if not accusing them: "What will you do?" he seems to ask. "How will you respond to the unjust treatment of this woman?"

That is the key question: What will the viewer do? Will the reader of the parable or the viewer of Millais' image be moved into action in ways that reflect Jesus' vision of divine justice and our roles in it?

The Gospel of Luke attempts to make the case that the parable provides an argument from the lesser to greater: If an unjust judge is willing finally to administer justice to this woman, how much more is the merciful God eager to do so for those who pray? But the chasm between this unjust judge and a gracious God who hears the prayers of the oppressed and acts in loving response to them is an interpretive leap too far. As Barbara Reid notes, Luke's comparison to fervent prayer "sidetracks the reader" from the parable's core message of relentlessly seeking justice, leading many interpreters of the parable to overlook its main point.

The unjust judge serves as an example of how all too often — in Jesus' time and our own — justice is not blind, that what passes for justice is unevenly and unfairly administered. Similar to the ancient law code of Hammurabi that established different laws for different groups of people, there often is a separate set of expectations for the wealthy and privileged, and a contrasting set of expectations for other groups.

In Jesus' parable, because of first-century patriarchal systems, gender plays a role in the judge's mistreatment of the widow, despite the fact that Jewish law required judges to give precedence to widows and orphans. The unjust judge's initial refusal to respond to the widow's case thus illustrates some of the structural and other injustices people faced in their daily lives throughout the Roman Empire.

"The Unjust Judge and the Importunate Widow" (1864), created by John Everett Millais, engraved and printed by the Dalziel Brothers (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Today, headline after headline in the news painfully remind us that unequal treatment of our fellow human beings — inside and outside the legal system — still exists, including gendered (in)justice, but also discrimination because of race, ethnicity, nationality or any other boundaries that human beings erect between themselves.

Although the Bible most often presents widows and orphans as deserving much-needed protection, this widow is active, even aggressive, on her own behalf — similar to a few notable widows in the Bible, such as Tamar, Ruth, Abigail or Judith.

In the surprise ending, because of the woman's pursuit of justice, the judge who does not fear God apparently begins to fear the widow; he even uses a boxing term for what she might do to him: "Wear me out" could be translated as "give me a black eye."

Jesus' portrait of this tenacious widow thus provides a paradigm for how, in the words of the civil rights hero John Lewis, to make "good trouble" by modeling the behavior Jesus demands from his followers: seeking, pursuing and demanding justice.

As is often the case, especially when women characters are involved, the Gospel of Luke tends to domesticate Jesus' parables, in this instance reducing the widow's militant advocacy for justice as symbolizing the necessity for fervent prayer.

Strikingly, Millais' image also reflects, in part, the domestication of the woman's aggressive actions by situating her in a prayer-like, prone position of supplication that heightens the pathos but detracts from the recognition of her agency. Thus Millais, like Luke, can "sidetrack" the viewer to some extent, but the engraving still captures her relentless, persistent pressing for justice. The image, primarily by the man staring at the viewer, vividly conveys the urgent need to respond to the widow's demand for justice; yet, like Luke and most other interpreters, it does not effectively portray the way in which Jesus envisioned the persistent widow as a paradigm for action.

The parable of the persistent widow unrelentingly pursuing justice from an unjust judge is best seen as an example of not how our prayers for justice should be continuous — although they should be — but instead as a paradigm for how we should unrelentingly pursue justice for those denied justice in our society, with a reminder that justice should not only be fair and equitable; it should be compassionate and restorative.

Recovering the radical message of Jesus' parable means that we should both recognize the widow as causing "good trouble" and realize that she should not be acting alone.

All 20 images created by John Everett Millais (1829–96) for his 1864 book The Parables of Our Lord, engraved and printed by the Dalziel Brothers, may be found online at Tate London.