Detroit Auxiliary Bishop Tom Gumbleton is seen with St. Joseph Sr. Elena Jaramillo and folkloric dancers at La Pequeña Comunidad in Nueva Esperanza, El Salvador, in 2015. (Courtesy of SHARE El Salvador)

Forty-one years ago, I met Tom Gumbleton at a peace symposium sponsored by the Sacramento Diocesan Justice and Peace Office headed by former Maryknoll Sr. Georgia Lyga.

Hundreds of mostly lay men and women packed the church auditorium. Tom spoke on the landmark 1983 U.S. bishops' pastoral letter on war and peace, the threat of nuclear annihilation, and the immoral costs of the military industrial complex.

I had just returned from El Salvador as a member of the SHARE Foundation board, and spoke about El Salvador, the U.S.-sponsored wars ravaging Central America, the influx of refugees in the United States and the emerging Sanctuary Movement — sharing the moral (and legal) imperative to provide safe haven to those fleeing war and to stop U.S. intervention.

Tom was 53 years old. I was 28. It was the beginning of a deep friendship and partnership in the struggle for peace with justice in our world.

I quickly discovered that Tom was cut from a different cloth: a bishop who not only listened (and listened deeply) to me, a young woman in the church (a radical act then as now) — but one who made decisions based on deep reflection and study, guided by the social Gospel, the prophetic tradition and the lived experience of those he accompanied. A rare trait indeed.

Tom's choices were deeply pastoral decisions. He gravitated to those who suffered the violence of war as well as structural violence of economic and political models that excluded the vast majority of the world's people. He was inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.'s vision of the beloved community and commitment to nonviolent direct action.

Tom, who died April 4, 2024, at age 94, used his office and position unlike any other to give voice to those he saw as sisters and brothers who were ignored and/or oppressed. He said yes to countless invitations to examine the root causes of world events, to place his hand in the open wounds of those who suffered, and to challenge the complicity of his country and church, even when doing so placed his standing in his country and the institutional church at risk.

Tom understood Dietrich Bonhoeffer's "cost of discipleship." He was inspired by Salvadoran Archbishop St. Óscar Romero's recognition that "If they kill me, I will rise in the Salvadoran people." He was a peacemaker in word and in deed.

His solidarity with the peoples of Central America provides a window into his approach and his courage.

Not long after we launched the Sanctuary Movement on March 24, 1982, the second anniversary of Romero's death, Tom supported the movement when only a handful of bishops did (including Archbishop John Quinn in San Francisco) and when the U.S. bishops' conference cautioned bishops against declarations of sanctuary.

Advertisement

Tom challenged U.S. foreign policy not only in El Salvador and Guatemala, but in Nicaragua, where the U.S. illegally armed and supported the Contras. In 1987, when I was executive director of the SHARE Foundation, Tom accepted our invitation to join the steering committee of SHARE's "Going Home" Campaign.

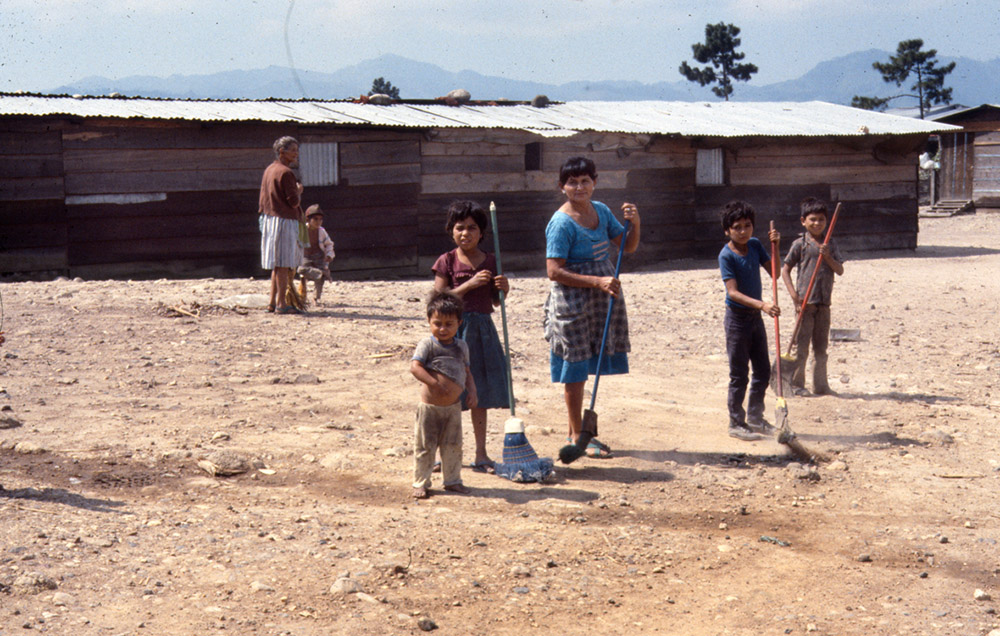

The task: to accompany 10,000 Salvadoran campesinos who had been forced to flee their homes amid saturation bombings and who longed to return to their villages after living in the confines of refugee camps in Mesa Grande, Honduras. The U.N.-sponsored camps were located on a remote, expansive flat space, dotted with hundreds of temporary tents erected on a dusty, chalk-like surface surrounded by a cyclone fence perimeter and patrolled by the Honduran military. Months of displacement had turned into years.

The repatriation was not supported by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, which deemed repatriation as too risky since the refugees' homes of origin were in "zones of conflict." The Salvadoran and Honduran governments and militaries opposed the repatriation, as did the U.S. government and U.S. military advisers.

But the Salvadoran refugees were determined. They made a direct appeal to the SHARE Foundation and the Interfaith Office on Accompaniment to accompany them in what became one of the largest nonviolent direct actions of the war — a movement to repopulate their homes, cultivate their lands, and reclaim the peace by their presence. In short, to stop the bombs.

The Mesa Grande refugee camp in Honduras in 1987 (Wikimedia Commons/Linda Hess Miller)

They invoked the Exodus story — a people of faith defying Pharaoh (the Salvadoran military) by organizing the beloved community with the strength of Moses (Romero) as wind upon their backs.

We at the SHARE Foundation were determined to meet in person with the refugees themselves, in Honduras. This was just one of the many times Tom said yes to join us in the endeavor. He braved the trip to Mesa Grande with me and the Rev. John Moyer, the executive director of the Northern California Ecumenical Council.

We rented a car at the airport and wound our way to Mesa Grande on unpaved roads. By the time of our arrival, we were met with one hurdle after another to secure the required permits to gain entry to the camp.

We were buoyed by the support of Salvadoran Lutheran Bishop Medardo Gómez and the head of Diakonia, Dimas Vanegas, who traveled from El Salvador to meet us outside the camps.

Even then, the military authorities imposed a late requirement to secure the written support of the local Honduran bishop before granting us access to the camps. The new condition required a nighttime drive to the town where he lived — a good distance away under a threatening storm.

After surviving a torrential downpour and lightning strikes on those same unpaved roads back to the bishop's town, we found the bishop at a private party. Though he took time to meet us, he initially questioned our credentials until Tom flipped into Latin to convince him of our bona fides.

We returned to the refugee camp the next day, with the bishop's signed letter of support in hand. We gained entry and met with the refugees' leadership and hundreds of refugees under pelting rain.

Tom listened, expressed our solidarity and won their hearts. And, of course, they won his. With Tom's unwavering support, over the next two years, the SHARE Foundation and the Interfaith Office on Accompaniment organized religious delegations to accompany more than 10,000 men, women and children through four successful repatriations.

Throughout that effort, U.S. and Salvadoran authorities sought to intimidate and undermine those of us active in repatriation — especially Tom. But their tactics failed.

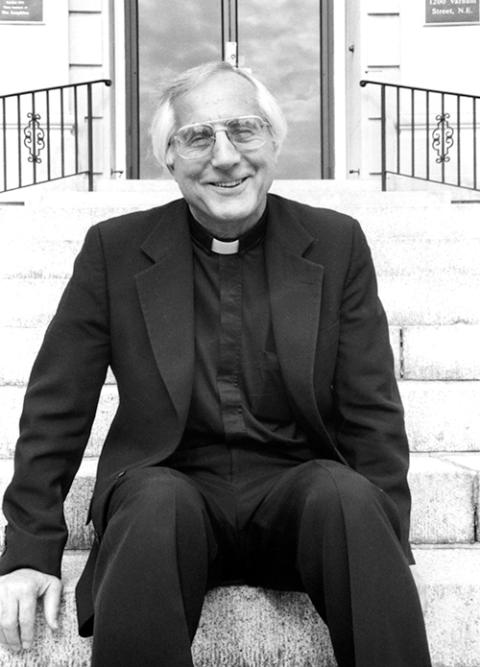

Detroit Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton in 1995 (NCR photo/Arthur Jones)

In 1990, Tom participated in a SHARE Foundation delegation to El Salvador two weeks after the Salvadoran military bombed the repopulated community of Corral de Piedra, recently renamed Ciudad Ignacio Ellacuría in memory of the slain Jesuit rector of the Catholic university who had been assassinated a few months earlier along with his five Jesuit brothers, and Elba and Celina Ramos.

Under the bombs in Corral de Piedra, four children and one adult had been killed. Sixteen others were wounded. Tom and the delegation faced off with the military who attempted to stop them from meeting with the community. The delegation persisted and met with survivors.

When he returned to the U.S., Tom wrote in the National Catholic Reporter, "A friend with whom I shared the experience of Corral de Piedra reminded me that the big picture of injustice is made up of a million tiny snapshots of a dying child, a tortured father, a grieving mother. ... When enough of us allow the memory of the unjust death of one child to inform our convictions and set our priorities, we will demand a moral society."

Not long after, SHARE sponsored a 14-city us tour by Jesuit Fr. Jon Cortina, who spent years working to find children missing after El Salvador's civil war. Tom and the Detroit Central America Committee hosted Jon to promote support for the repatriated communities rebuilding their lives.

In my introduction of Father Jon, I shared that, in El Salvador's repopulated communities, when people are asked about Romero, they say, "He's alive. He lives in Detroit" — a reference to Bishop Tom Gumbleton.

For years after the Salvadoran Civil War ended in 1992, Tom continued visiting communities there, accompanied by his longtime confidant, partner and president of the SHARE Board, Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Sue Sattler; Bill and Mary Carry; and Oscar Chacón.

Tom joined in the annual protests at the School of the Americas. He visited communities on the U.S.-Mexico border. He was a founding member of Pax Christi USA in the context of the Vietnam War and amplified his peace work in Haiti, in Iraq and across the globe.

Detroit Auxiliary Bishop Tom Gumbleton speaks to Jean Stokan, justice coordinator for the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, at La Pequeña Comunidad in Nueva Esperanza, El Salvador, in 2015. (Courtesy of SHARE El Salvador)

In 2015, on the occasion of the 35th anniversary of the killings of four U.S. church women in El Salvador, Tom joined a delegation co-sponsored by the SHARE Foundation and the U.S. Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR). José Artiga, by then executive director of the SHARE Foundation, led the group. Seventy-five women religious, laywomen and a few men made the pilgrimage to mark the ultimate sacrifice of Maryknoll Srs. Ita Ford and Maura Clarke, Ursuline Sr. Dorothy Kazel and laywoman Jean Donovan, and all those who died during the war.

Tom supported them at the same time the Vatican was completing its appalling investigation of U.S. women religious in general and LCWR in particular. Tom's capacity to empathize and bear witness to human suffering was matched by his ability to find joy in the resilience of the human spirit in the most hopeless of circumstances. Despair was not an option.

Tom was a source of profound hope for the communities with whom he worked. He, in turn, was nourished by their love and courage. We give thanks for the life and love of our brother — a beautiful priest, a dear friend, a brave and compassionate heart, a brilliant mind, a rare leader who used his position to advance authentic peace and justice.