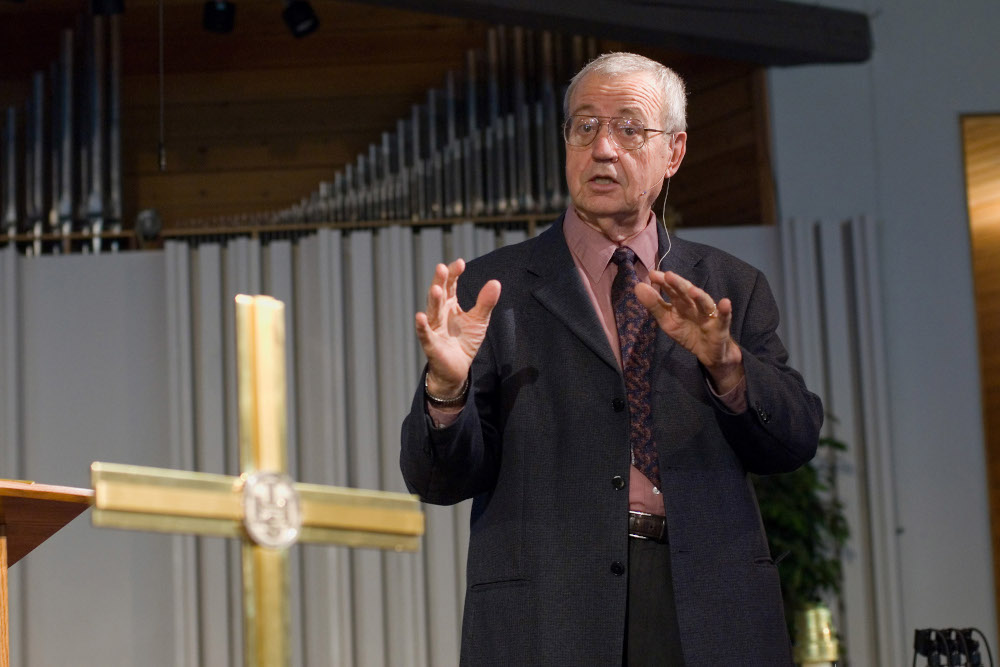

Dallas Willard gives a Ministry in Contemporary Culture Seminar at the George Fox Evangelical Seminary in Portland, Oregon, in 2008. (Wikimedia Commons/Loren Kerns)

Advent is a time for renewal, a time of new beginnings. It is, after all, the start of a new liturgical year, which brings with it an opportunity for personal assessment and even goal-setting akin to the start of a new calendar year and the tradition of New Year's resolutions. Advent is a beloved season but also one that presents several challenges, especially given the time of year during which it occurs — the height of holiday stress.

Each Advent I try (emphasis on try) to do something to help me stay focused on the liturgical season, to keep it within my sights as so many competing interests converge — the pressure to buy gifts for loved ones, the increasing ministerial obligations, the end-of-the-semester grading and so on — to distract and discourage any substantive spiritual renewal. This year, I found myself drawn to exploring the writings of a Christian spiritual writer I had not heard of until just a few months ago.

Dallas Willard, the longtime professor of philosophy at the University of Southern California who died in 2013, was perhaps best known for his writings on modern Christian discipleship and spirituality. If my informal conversations with Catholics over the last few months are any indication, he is largely unknown among Catholic readers. But many of those in evangelical and other Protestant circles have known and loved his work for decades.

Advertisement

Last weekend, when asking a few Franciscan friars if they had heard of Willard before and getting an unsurprising "no" response in return, I described Willard as something like a "Protestant Ronald Rolheiser," a comparison that I hope both brilliant and inspiring authors would appreciate. Like Rolheiser, who holds a doctorate in systematic and philosophical theology but also writes accessibly, beautifully and with depth about the Christian spiritual life, Willard's early academic formation was as a philosopher who studied phenomenology and translated several important texts by the important German scholar Edmund Husserl. Also like Rolheiser, Willard was able to speak beyond the "ivory tower" of academia to touch not just the minds, but also the hearts and souls of thousands, if not millions, of spiritual seekers.

It was kind of eerie — or perhaps, providential — that a handful of bright and spiritually mature Christian ministers happened independently to mention Willard to me over the course of several months. In an effort to be attentive to the Holy Spirit working through others, I took this as a sign that I should check out some of Willard's writings.

Although I have only surveyed a few of his many books, articles and recorded lectures, I was drawn immediately to the recurring theme of discipleship. He rightly believed that all the baptized are called to be disciples of Jesus Christ, not just "Christians."

That may appear as a distinction without difference but, as Willard frequently observes, the conflation of "being a Christian" and "discipleship" is a widespread problem. Most people use those two terms interchangeably. But unlike the nominal adoption of the term "Christian," being a disciple requires becoming a student, an apprentice, somebody who is actively learning from and being formed by a teacher or mentor.

An Advent wreath is pictured in the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican Dec. 15, 2014. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Most self-identified Christians, of whatever denomination, appropriate the term as a label or static noun. But what Jesus of Nazareth invited people into was not an ideological category or political party or social affiliation, but a way of being in the world. Jesus called those who would be his followers to an experience of ongoing conversion, a lifelong commitment of change and development aimed at living the gospel and striving to follow the will of God.

Recognizing the urgency of this call, Willard says early in his book The Great Omission: Reclaiming Jesus's Essential Teachings on Discipleship:

So the greatest issue facing the world today, with all its heartbreaking needs, is whether those who, by profession or culture are identified as "Christians" will become disciples — students, apprentices, practitioners — of Jesus Christ, steadily learning from him how to live the life of the Kingdom of the Heavens into every corner of human existence.

My reading of Willard's reflections on the gospel and the Christian call to take more seriously our baptismal vocation is exactly what I need to enliven this Advent season. It is an inspiring reminder of the basics of gospel living that Pope Francis, among others, has continually called all Christians to embrace.

Willard writes in The Great Omission:

As disciples (literally students) of Jesus, our goal is to learn to be like him. We begin by trusting him to receive us as we are. But our confidence in him leads us toward the same kind of faith he had, a faith that made it possible for him to act as he did. Jesus's faith was expressed in his gospel of heaven's rule, the good news of the "Kingdom of heaven" (Matthew 4:17).

This is a message that church leaders and ordinarily Christians alike need to hear. All of us, especially those of us in affluent societies and comfortable contexts like most in the United States, can become too complacent and self-assured when it comes to what it means to be a "good Christian." But in truth, it is very easy for self-identified Christians to mistake themselves for the master and teacher instead of the novice and student. How quick we are to assume that so many years of Catholic education or religious formation or daily Mass attendance constitutes the conclusion of our Christian education.

All of us, especially those of us in affluent societies and comfortable contexts like most in the United States, can become too complacent and self-assured when it comes to what it means to be a "good Christian."

But Willard brilliantly reminds us that to be a Christian disciple means committing ourselves to being students of Christ. He is the true teacher, the authentic "life coach," the personal and professional mentor we ought to seek, at least for as long as we dare to call ourselves Christians.

In his 1997 book The Divine Conspiracy: Rediscovering our Hidden Life in God, Willard summarizes well the practical implications of what it means to recognize Christian discipleship as the experience of living as students of Jesus Christ. He writes:

Another important way of putting this is to say that I am learning from Jesus to live my life as he would live my life if he were I. I am not necessarily learning to do everything he did, but I am learning how to do everything I do in the manner that he did all that he did. … My discipleship to Jesus is, within clearly definable limits, not a matter of what I do, but of how I do it. And it covers everything, "religious" or not.

Willard is certainly not the first nor, I hope, the last to emphasize this point about the need for a more honest look at how we are or are not taking seriously our claims as Christian disciples. But his intelligent, accessible and inspiring style of writing is exactly what I needed this Advent. I appreciate his turns of phrase, his breaking open the scripture and his consistent challenge to take seriously what it is we say we are about to become who we claim to be.

It's never too late to enroll as the students we are in the continuing education of Christian discipleship, especially during the season of Advent. So, if you're looking for a syllabus or reading list to inspire you along the way, you too might check out the writings of Dallas Willard.