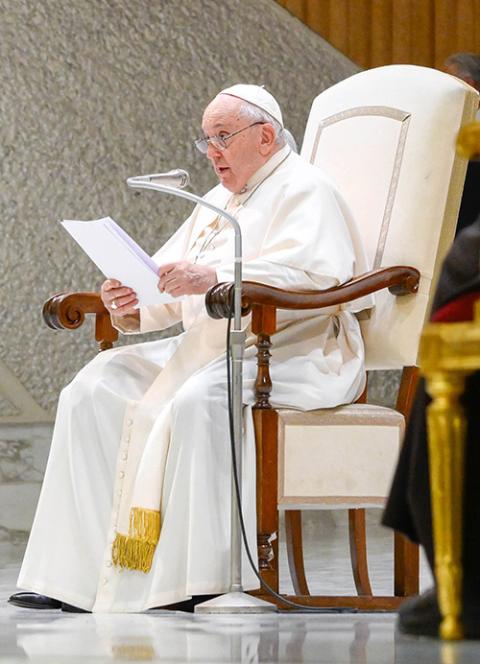

Pope Francis speaks to visitors gathered to pray the Angelus in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Oct. 29. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

Pope Francis recently issued a short apostolic letter motu proprio titled "Ad Theologiam Promovendam." The text introduces new statutes for the Pontifical Academy of Theology and, in so doing, captures some of the essential reforms Francis has initiated.

In a sense, this document achieves at the theoretical level what the Holy Father said in a more specific form in his recent responses to some dubia submitted by five intransigent cardinals. It was not simply that the pope suggested the questions posed by the cardinals were too small, but that they were poorly focused, abstract and removed from any concern with whether their singular focus on doctrinal clarity would help bring people closer to the Lord.

Standing behind both the papal response to the dubia and this latest motu proprio is the attitude shown by Jesus toward the Pharisees in Chapter 23 of St. Matthew's Gospel, which we heard this past Sunday: "For they preach but they do not practice. They tie up heavy burdens hard to carry and lay them on people's shoulders, but they will not lift a finger to move them. All their works are performed to be seen."

This new document has a particular focus, the Pontifical Academy of Theology, and so the language the Holy Father uses is like a conversation that starts at 60 miles per hour. "Theological reflection is therefore called to a turning point, to a paradigm shift, to a 'courageous cultural revolution' (Laudato Si', 114) that commits it, in the first place, to being a fundamentally contextual theology, capable of reading and interpreting the Gospel in the conditions in which men and women live daily, in different geographical, social and cultural environments, and having as its archetype the Incarnation of the eternal Logos, his entry into the culture, the vision of the world, the religious tradition of a people," Francis writes.

Advertisement

Even the language that calls for avoiding abstraction ends up sounding a bit abstract in a text like this!

Still, the pope's intention is clear: Theology, like doctrine, must serve the church's primary goal, the salvation of souls. To achieve this, it must be engaged in the world it seeks to evangelize, and not just engaged intellectually.

As Cardinal Francis George discussed years ago, we must love a culture in order to evangelize it. Asked about that observation in an interview at the time his book The Difference God Makes was published, the cardinal replied, "The reason why it is important to love the culture is because it is in us. If you hate your culture, you hate yourself. Self-hatred is not an evangelical virtue."

I do not know if Francis ever read those words, but he would have smiled if he did.

Mindful of the fact that we Americans tend to be myopic about papal texts, viewing them as directed at us and our ecclesial situation, nonetheless it is impossible not to conjecture whether or not the person drafting this new document, or the pope himself, included the reference to a "paradigm shift" in response to George Weigel's 2018 column at First Things that was titled "The Catholic Church Doesn't Do 'Paradigm Shifts.' " But, as I say, that would be myopic.

The pope cites Veritatis Gaudium, the 2017 apostolic constitution on ecclesiastical universities and faculties. There, Francis quoted from a talk he had given to an International Theological Congress in Argentina in 2015: "One of the main contributions of the Second Vatican Council was precisely seeking a way to overcome this divorce between theology and pastoral care, between faith and life."

Again, we see all of Francis' reforms rooted in the ongoing reception of Vatican II. His comments put me in mind of the 2021 meeting of Hispanic theologians in which theologians from academic settings were consciously brought together with theologians working in pastoral assignments.

Pope Francis speaks to people taking part in a meeting organized by the Catholic Charismatic Renewal International Service in the Paul VI Audience Hall at the Vatican Nov. 4. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Emphasizing this "relational dimension" in which the pope thinks theology must be undertaken, Francis writes:

It is the approach of cross-disciplinarity, that is, interdisciplinarity in the strong sense, distinct from multidisciplinarity, understood as interdisciplinarity in the weak sense. The latter certainly favors a better understanding of the object of study by considering it from several points of view, which nevertheless remain complementary and separate. Cross-disciplinarity, on the other hand, must be thought of "as situating and stimulating all disciplines against the backdrop of the Light and Life offered by the Wisdom streaming from God's Revelation" (Apostolic Constitution Veritatis Gaudium, Preface, 4c).

This section is critical and many theologians should spend a great deal of time unpacking it.

One word of caution: The social sciences are not always the best dialogue partners for theology. Again, looking only at the situation here in the U.S. So much of social science and the humanities is now done in the shadow of deconstructionism which robs meaning from our culture. Catholic theology must operate in the shadow of Vatican II.

The core difference is this: Deconstructionist theories all seek to analyze power relations in one way or another. Catholic theology analyzes the "signs of the times" by looking for evidence of grace. I have come to believe that this is the foundational issue hindering our ability to evangelize our culture.

The pope insists that theology engage in "dialogue within the ecclesial community and an awareness of the essential synodal and communion dimension of doing theology." In addition to the meeting of the Academy of Catholic Hispanic Theologians of the United States noted above, I would commend (again!) Susan Bigelow Reynolds' recent book People Get Ready: Ritual, Solidarity, and Lived Ecclesiology in Catholic Roxbury, which I reviewed here. It evidences both dialogue with the ecclesial community and with other theological approaches.

In this same paragraph about dialogue, the pope concludes: "It is therefore important that there are places, including institutions, for living and experiencing collegiality and theological fraternity."

It has been one of the great blessings of my life to have been affiliated with on-campus centers or think tanks, such as the Center for Catholic Studies at Sacred Heart University where I am now a fellow. Collaborating with other such centers as the Hank Center at Loyola Chicago, the Center on Religion and Culture at Fordham University and the Boisi Center at Boston College, has allowed me to see some of this "collegiality and theological fraternity" lived out. In an increasingly siloed academic culture, these centers are, as Francis realizes, vital for reaching across disciplines.

There are other key points in this document that need to be teased out by theologians in the days and weeks ahead. This text exemplifies what I said about the just-concluded first session of the synod:

For reasons some find inadequate and others necessary, the first three post-conciliar popes all discerned the need to restrain some of the centrifugal forces unleashed by Vatican II. Francis recognizes that the full reception of Vatican II depends on reengaging, maybe even encouraging, those centrifugal forces.

The pope is clearly trying to steer the church into the wind, as it were, and that wind is Vatican II.