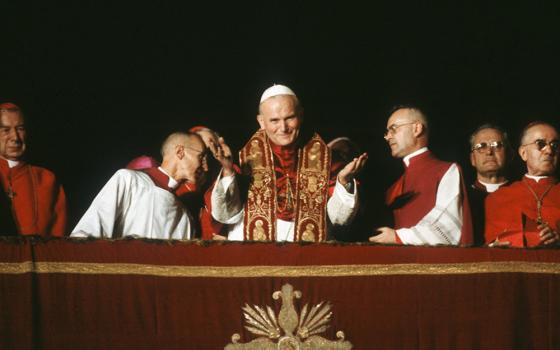

San Salvador Archbishop Arturo Rivera Damas (near center with stole) and others view the bodies of those slain at Central American University in El Salvador Nov. 16, 1989. (AP/John Hopper)

Editor's note: To celebrate our 60th anniversary, we are republishing articles from our archives. Find more articles here.

This installment of NCR's 60th anniversary feature exemplifies the crucial role NCR has played in the media landscape since 1964. In the news report originally published Nov. 24, 1989, readers learn about the shocking massacre of Jesuit priests at the Central American University in San Salvador, which had occurred eight days earlier.

(NCR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Thirty-five years later, the killings remain news and NCR once again is on top of the story. Rhina Guidos, Latin American regional correspondent for the Global Sisters Report, wrote for NCR on Nov. 21 that El Salvador ordered former president Alfredo Cristiani and 10 others to stand trial for the killing of the six priests, their housekeeper and her daughter — murders now considered war crimes.

We are proud of our legacy of reporting on the church and the world with rigor and independence. And most of all, we are grateful to those of you who have been by our side along the way.

Nov. 24, 1989

Fear, accusations and multiple arrests follow Jesuit murders in El Salvador

From News Services and NCR Staff

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador, and WASHINGTON - Six Jesuit priests, including top officials of the Central American University, along with their cook and her teenage daughter, were slain on the grounds of the university Nov. 16 by as yet unidentified assassins.

The next day, members of the Salvadoran National Guard arrested and took to Treasury Police headquarters at least 14 foreign missioners and activists, many of whom had only recently come to El Salvador, as they gathered in a Lutheran church.

Solemnly gazing on the bodies of the slain Salvadorans, San Salvador Archbishop Arturo Rivera Damas said: "As if 70,000 dead are not enough for them," but Rivera made no direct accusations. "In no way are we in a position" to blame specific individuals or groups, he said.

The assassinated Jesuits included university rector Father Ignacio Ellacuria, vice rector Father Ignacio Martin-Baro, and head of the university human-rights office Father Segundo Montes. The others were identified as Fathers Juan Moreno, Amando Lopez and Joaquin Lopez y Lopez. Also killed in the Nov. 16 early morning attack were the cook, identified as Julia Elba Ramos, and her 15-year-old daughter, Celina, who worked at the home of the slain Jesuits.

Back in Washington Nov. 17, El Salvador's ambassador to the United States, Miguel A. Salaverria, also did not specifically lay blame on any one group but implied that the assassinations could have been the work of the rebels.

The ambassador said that one of the murdered priests, Ignacio Ellacuria, known as a critic of the Salvadoran government, had recently written "that President (Alfredo Cristiani) was successful in his first 100 days in office." (Cristiani, head of the right-wing ARENA party, took office in June.)

Continued the ambassador, statements supportive of the El Salvador government by one of its frequent critics, such as Ellacuria, "can make a man expendable for the guerrillas." He said that "that is the general opinion in El Salvador" regarding the priests' deaths.

In testimony Nov. 17 before the Senate subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, the U.S. Catholic Conference's Robert T. Hennemeyer told the subcommittee "that the vigorous and successful investigation and prosecution of the murderers of the six Jesuit fathers and the two women (should) be taken as the test of (the Salvadoran) government's resolve" on human rights.

Hennemeyer repeated Rivera's call "for at least an immediate cease-fire or truce to enable the Red Cross to evacuate the wounded and bring desperately needed supplies of food and medicine to communities most affected by the fighting."

Later in the hearing, as Samuel Dickens of the American Security Council testified in defense of the Salvadoran military's actions, protesters shouting "Stop the bombing! Stop the war!" were removed from the hearing room.

Advertisement

Several senators indicated that U.S. military aid to El Salvador would be endangered if human-rights abuses are tied to the government or the military.

In El Salvador, at the killing site, however, there is a different version. There, a sign says: "This is punishment for the sympathizers of the FMLN," the initials by which the Salvadoran rebels are known.

According to a priest in San Salvador who requested anonymity, on Nov. 16 armed men entered the Jesuit university early in the day, took their victims into a garden and shot them. Spent shells and automatic rifles, said to be from U.S.- made M-16s, were strewn about the area where the bodies lay, the priest said. Evidence indicated a pipe bomb had been used to cover the sound of shooting. In one room of the residence, 25 spent shells were found.

Said one senior Western diplomat, "You have to assume that the killings were done, if not by the army, then certainly by the people who have the freedom of movement (during curfew) that only the army bestows."

The Jesuit provincial for Central America, Father Jose Maria Tojeira, was quoted by the Associated Press as saying the victims were "assassinated with great barbarity." "For example," he said, the assailants "took out their brains."

The killings came on the fifth day of intense fighting between rebels who had launched a major offensive in the city and government troops.

In Washington, Jesuit Father Joseph Hacala of the Jesuit Office of Social Ministries also stated, "We have no definite proof" of who was responsible for the assassinations. Hacala has been in contact with the Jesuit provincial in El Salvador, other Jesuits in El Salvador and the Jesuit headquarters in Rome. Salvadoran government troops were close to the Jesuit residence at the time of the killings, according to Hacala's sources.

The Associated Press reported Nov. 17 that, according to witnesses, "30 men in army uniforms entered the priests' residence just before the shooting began."

"It should be noted," said Eileen Purcell of the Washington-based Share Foundation, which raises funds for Salvadoran refugees, "that this was not an anonymous attack." Two of the priests, said Purcell, "were under fire every single day in the national government print presses and on radio- it suggests the complicity of the government in their death."

In Rome, Father Alvaro Restrepo, a Jesuit assistant for Latin America, said the Rome headquarters had received information, based on eyewitness accounts, that the gunmen were in uniform. He said that would raise a "strong suspicion" that government soldiers were involved.

He called for a "careful investigation" of the shooting. Restrepo said the house where the Jesuits lived had apparently been searched by army soldiers one or two days before the assassinations.

In a statement, Jesuit officials in Rome condemned the killings as an act of "barbarian violence" and called for respect for the life of other church people who have been threatened.

The statement said Jesuit superior general Father Peter Hans Kolvenbach learned of the killings in a phone call 15 minutes after the bodies were found. Jesuit officials in Rome said some of the bodies had been badly disfigured by machine-gun fire, with more than 20 bullets found in the body of one priest.

"The order condemns this barbarian violence that has already caused so many other victims in El Salvador. It hopes and prays that the blood of these brothers was not spilled in vain," the statement said.

"It trusts that the lives and rights of so many other church people and Salvadorans who have been threatened will be respected and that a just peace will be respected in the conscience of everyone," it said.

Jesuit Father Fermin Sainz, psychology professor at the university, told NCR: "They (the dead priests) were people who sought peace with justice. They had nothing to do with armed struggle. They were people who had never touched a gun. The killers came to combat their ideas with bullets."

In a telegram sent Nov. 17 to San Salvador's Rivera, Pope John Paul II condemned the "abominable violence" against the Jesuits.

Four days before the attack on the priests, San Salvador's Rivera had urged an end to the fighting. "Enough killing, enough bloodshed. Now more than ever we must put our faith in God and call for an end to the violence," he said in a Nov. 12 homily.

Rivera's wish was not to be. In a military offensive that began Nov. 11, guerrilla forces invaded San Salvador, striking government installations and taking control of as many as 25 neighborhoods in the metropolitan area. The actions coincided with strong attacks in other cities nationwide.

It was the most extensive fighting in the city in almost a decade. Using home-made missile launchers, guerrillas of the FMLN launched their offensive by attacking the presidential palace, the National Guard, the national police and the army's First Infantry Brigade, all based

in San Salvador.

Cristiani declared a state of siege over the country the evening of Nov. 12, and imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew in the capital. In a message broadcast over local radio stations, he denounced the FMLN as "an irrational, internationally backed force" that was terrorizing the population.