Bishops listen to a speaker Nov. 14, 2018, at the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

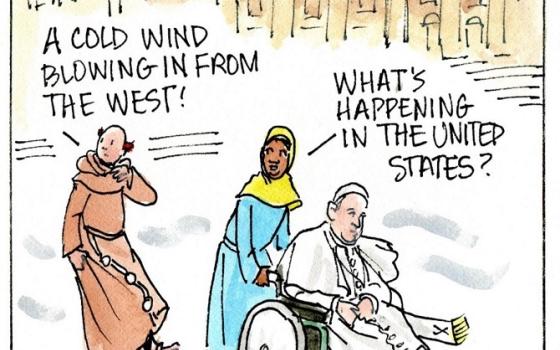

This morning, the U.S. bishops are gathering in regional meetings, instead of the usual opening public session at their annual plenary meeting. This afternoon (Nov. 14) they will hold their first session behind closed doors, in executive session, which normally would be held after two days of public meetings. These changes, it is hoped, will help the body of bishops begin to have the kind of conversations that can bridge the divides within the hierarchy.

The official agenda has not been released to the media, but we know they will be electing officers and committee chairs and discussing what to do about their quadrennial teaching document related to voting, "Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship," both of which I addressed in earlier columns. What else will they be discussing? What else should they be discussing?

The forthcoming Eucharistic Congress will get an update. Let's hope the bishops put a stop to some of the more foolish ideas that have come from the organizing committee. I was especially horrified by the idea that the organizers plan — according to four bishops familiar with the organizers' report — a kind of Olympic flame relay, only with the body and blood of Jesus Christ. This is not our tradition. It reeks of the kind of marketing approach that I feared all along. As much I take a perverse delight in watching conservative prelates practice inculturation, the sacraments should not be marketed. Let's hope some bishops have the courage to stand up and say, "No!" to this and other lousy ideas.

The bishops will discuss the crisis in Ukraine where Russia's unprovoked aggression continues to cause a humanitarian and political crisis of the first order. I understand the need for a witness to the Christian obligation to seek peace, but when you read statements by Catholic peace groups that unwittingly advance the Kremlin's propaganda effort, it is time for the bishops to remind the rest of us that there is a reason the dominant Catholic theological tradition is just war theory, not pacifism.

To quote George Orwell's famous essay "Pacifism and War," the problem is that in circumstances such as those faced by Ukraine today — and by the Allies in 1942, "so-called peace propaganda is just as dishonest and intellectually disgusting as war propaganda. Like war propaganda, it concentrates on putting forward a 'case', obscuring the opponent's point of view and avoiding awkward questions."

Advertisement

I hope the bishops pray for peace but lend their support to the Biden administration's willingness to rush as much military and humanitarian aid as we can to the brave people fighting against fascism in Ukraine.

Of course, it doesn’t make sense for the bishops to be concerned about the fate of democracy abroad and indifferent to its fate here at home. The U.S. bishops are heirs to a noble tradition of defending democracy. Cardinal James Gibbons' sermon when he took possession of his titular church of Santa Maria in Trastevere was a robust defense of America's constitutional separation of church and state at a time when the idea itself was considered heretical.

At the Second Vatican Council, Cardinal Francis Spellman brought Jesuit Fr. John Courtney Murray as his theological advisor, and Murray helped the conciliar theologians draft what became Dignitatis Humanae, the Declaration on Religious Liberty. The American bishops as a whole argued for that document and for the praise of democracy and human rights found in Gaudium et Spes. Other influences — the catastrophe of fascism, the writings of Jacques Maritain, the rise of Christian democracy in the postwar era — all helped lead the church to embrace rather than fear democracy.

These historical moments were not without complications. Throughout the long 19th century, and for readily understandable reasons, the Vatican has suspicious of, and hostile to, democracy in large part because most republicans were profoundly anti-clerical. The French Revolution really did produce thousands of martyrs. At Vatican II, Murray's promotion of negative liberty as a juridical concept was found lacking from the standpoint of theological anthropology, and the church's defense of religious liberty had to be reconceived in terms of positive freedom.

The current moment suffers from different complications: Can the conference find a way to give voice to the moral necessity of defending democracy without falling into partisanship? This has always been the difficulty with a singular focus on abortion at the expense of other life issues: Our witness ends up being partisan, which diminishes, even compromises, the transcendent quality of the church's moral witness. The last people bishops should look to for guidance on any issue, from abortion to LGBT rights to the environment, are activists who never stop to ask if their advocacy will strengthen or weaken the communion of the church and political strategists who hitch their laudable moral concerns to personal ambitions. Bishops need to be bishops.

Can the conference find a way to give voice to the moral necessity of defending democracy without falling into partisanship?

At a moment when the politics of the nation are so terribly polarized, the bishops need to think creatively about how they can witness to the various moral claims our Catholic faith demands without appearing to be complicit with the polarized, partisan divides. I confess I have no easy checklist on how to accomplish this. I would simply note that in the face of moral complexity, a good starting point is the maxim, first, do no harm.

There is no greater gift the bishops can impart to the Catholic Church in the United States, and no gift the Catholic Church can give to our nation, than to transcend their differences, not obliterating human variety or demanding any kind of fake homogenization, but being true to our name, Catholic and avoiding its opposite, sectarian.

There may be something more important than being right in every particular. Being together is, at this moment, the challenge to which our faith calls us. As a columnist, forbearance is not my specialty, but for the bishops at this moment, it is a first step towards a more fruitful witness in the public square, towards the vision of Vatican II, of the church as leaven in the world.

As it turns out, the Holy Father has given the bishops the means to achieve this with his calling for a more synodal church. People in parishes and dioceses across the country — and the world! — have been listening to each other. They have been able to agree to texts that accurately represent the concerns raised. Catholics have been able to discover that there are more postures available to the Christian than the defensive crouch. We can engage each other and, with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, find a unity we could not achieve on our own. That will take humility and what the Scripture calls "fear of the Lord."

Let's hope these are found in Baltimore this week.