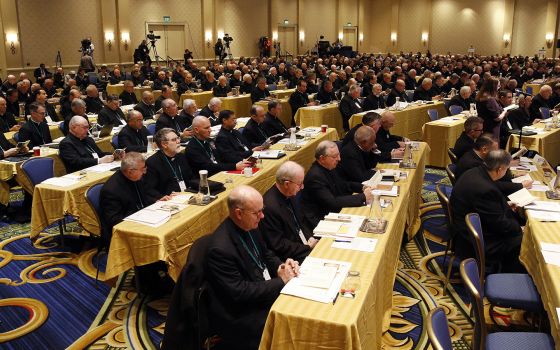

Bishops discuss a resolution to encourage the Vatican to release all documents related to the investigation of allegations of misconduct by Archbishop Theodore McCarrick Nov. 14 at the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

I am always glad to attend the bishops' conference meeting in Baltimore every November. I get to witness up close the debates that determine the shape and direction of the church in this country, I can visit with friends and colleagues in the religious press, and the crab cakes are always delicious. This year, the crab was still delicious, and it was good to see friends and colleagues, but what I witnessed was amateur hour at the U.S. bishops' conference.

On Nov. 12, Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, the president of the conference, expressed his disappointment when he announced the Vatican's decision to delay any votes on concrete proposals to confront the clergy sex abuse crisis. At the coffee break, bishops were fuming, complaining that Rome had pulled the rug out from under them. Even those bishops who are most enthusiastic about Pope Francis were distressed, worried that he did not understand the media spotlight under which the bishops were laboring.

But, when the bishops began discussing the proposals on Nov. 13, it quickly became obvious that the proposals were ill-conceived and would have fallen apart on their own, without any help from Rome. Erecting a national oversight commission, at considerable expense and with additional bureaucracy, to monitor 200 bishops, very few of them likely to have broken their vows of celibacy, didn't seem very practical once they began discussing it. The proposed commission would report allegations to the nuncio, but that happens now, and no one had bothered to ask the nuncio if he wanted a commission to help him in his work. The Standards of Conduct seemed poorly framed and vague. The whole thing seemed amateurish.

I understand the need for the laity to be involved. But, even this seemed botched. I want the bishops to go deeper than simply fixing norms to monitor sex abuse. The cover-up of the abuse is a symptom of a clerical culture that was erected in the 16th century to address key problems and which has outlived its healthy years. But, just as the reformers at the Council of Trent did not pay somebody else to do their work, the bishops today can't outsource the conversion that is needed to make that culture healthy. They must do the work, too.

It was kind of funny to see both a liberal reform group and a conservative commentator urge the bishops to dress differently, as if that would not be dismissed — rightly — as a silly PR stunt at best and a fraudulent attempt at genuine conversion at worst.

There was a lot of anger directed at former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, along with justifiable outrage that someone who lived a double life for so long and whose alleged depredations went on for so long, could have risen so high in the hierarchy. But, frankly, looking around the room, almost everywhere you looked, you saw evidence of the often lousy appointments to the episcopate that stalked the reigns of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Advertisement

McCarrick may have preyed on seminarians, but San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone preyed on some people's homophobia in calling attention to a study — I use the term loosely — by Fr. Paul Sullins, who used to teach at Catholic University of America, that claimed to demonstrate a link between homosexuality in the clergy and clergy sex abuse. The study is bunk.

Previously, I had only heard Sullins distort Catholic social teaching, but apparently he is willing to cherry pick data to make a tendentious sociological case — and construct an easy scapegoat. Cordileone bought it.

McCarrick may have lived a double life, but what to make of the crimped piety of Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, who spoke movingly about the vocation of a Christian bishop before waltzing over to a rally being held by hate-filled Michael Voris and Church Militant where guests were greeted by signs calling on all homosexual clergy to resign and touting Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò as a "hero." Strickland should be able to smell the venomous hatred coming from that crowd of anti-gay bigots.

My old friend from seminary, Bishop Michael Olson of Fort Worth, Texas, spoke with emotion in his voice as he called out his brother bishops for not even disinviting McCarrick from future meetings. McCarrick is, on the pope's orders, living in a monastery far, far away. But, Bishop Robert Finn, formerly of the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, was sitting right there. The allegations against McCarrick have not been proven in a court of law nor in an ecclesial trial, but Finn was convicted of a misdemeanor. Why was Olson so keen to attack McCarrick and not Finn? I was glad Olson called on the body to repudiate Vigano's call for the pope to resign, but why not repudiate the whole "testimony"?

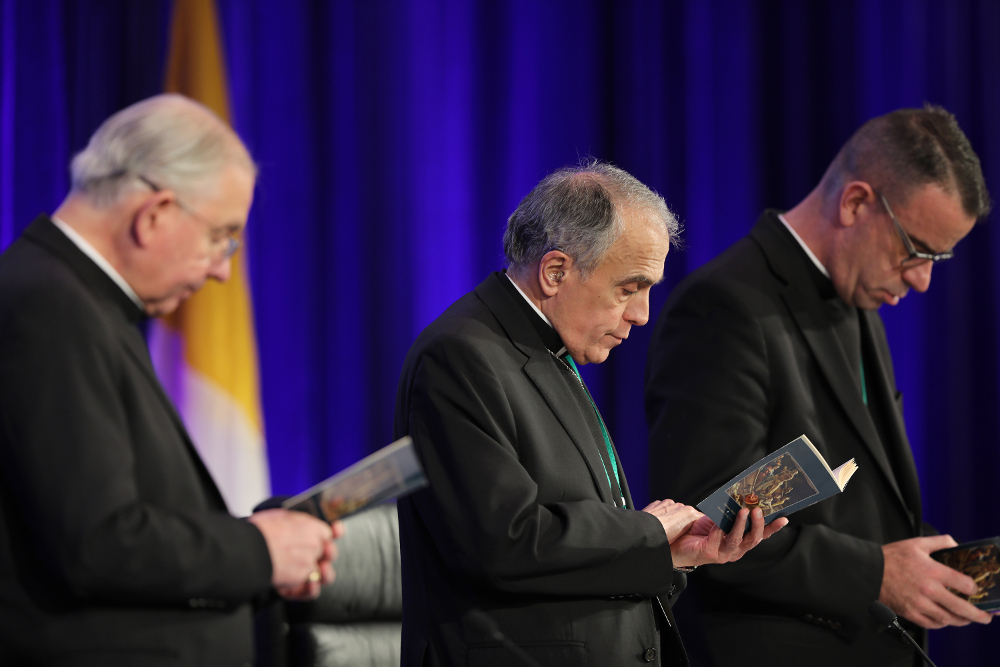

DiNardo should resign as president of the conference. There was no leadership on display before the meeting nor at it. In 2002, at Dallas, Atlanta Archbishop Wilton Gregory was the president of the conference and he worked the room, consulting with his brother bishops extensively. Gregory is a born leader who tirelessly explained what was going on to the press corps whose job it was to communicate the Dallas decisions to the world. DiNardo did not even show up at the press conference on Nov. 14 to take questions, and there are plenty we had for him.

The prelate who came closest to putting his finger on the problem was Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey. On Nov. 13, he said that he had experienced the sense that the bishops have lost their credibility, in his own ministry and from listening to his brother bishops, and that a question came to him while he was waiting to speak. As bad as the events of the summer of shame were, what was there before if their credibility could be lost so quickly?

Cardinal Daniel DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, center, leads afternoon prayer Nov. 14 during the bishops' fall general assembly in Baltimore. Also pictured are Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles, vice president, and Msgr. Brian Bransfield, general secretary. (CNS/Bob Roller)

I think this is the question the pope wants them to ask: Whence your credibility as a bishop? I think the Holy Father knows that there will always be sickos and perverts, but what turned isolated instances of horrific behavior into a crisis was the clerical culture that sought to protect itself rather than to protect children, that worried about scandal more than harming children. That is what has to change. There will always be some priests and some teachers and some boy scout leaders who try and sexually abuse a child. The question is how should ministers of the Gospel respond? And, while there will always be some ministers who are clueless or nasty, how could a culture form that such patterns of evil behavior covering up the crimes of the perpetrators were so widespread?

Here, as well, Pope Francis is going to have to step up to the plate and explain the behavior of his predecessor, St. Pope John Paul II. He set the patterns that became the rule by refusing to meet with victims and denying the allegations unheard. He made it near to impossible to laicize criminal pedophiles, and he, not to put too fine a point on it, promoted McCarrick not once, not twice, but three times. John Paul was a mystical and holy man, and I do not doubt his aides kept important information from him. Holy he was, but "the Great"? When he was not capable of seeing past his aides' obfuscation?

And if McCarrick had to surrender his red hat, surely there are two other red hats that should be retired, those belonging to Italian Cardinal Angelo Sodano and Polish Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, the former Secretary of State and personal secretary to John Paul II, respectively. They knew. They had to know. And not just about McCarrick.

In a few short months, the presidents of the world's bishops' conferences will converge on the Vatican to discuss the issue of clergy sex abuse. The Holy Father has a few short months to prepare a meeting of singular consequence. He must consult with bishops who not only understand the problem but can exercise some competence and wisdom in devising proposals to confront it.

By then, the U.S. bishops will have had their retreat and we will see what effect that has. I suspect for some of them, the ones who believe they have already solved all the riddles of revelation and for whom the reduction of religion to ethics, thence to legalisms and finally to politics is complete, for them, they really will need to fall off a horse before they get it.

Far be it from me to presume. Perhaps the Holy Spirit will inspire them to conversion in new and profound ways. We can hope. Indeed, at the conclusion of the bishops' meeting in Baltimore, hope was really the only thing we have to hold on to. Maybe that is the lesson the pope wanted us all to learn.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.