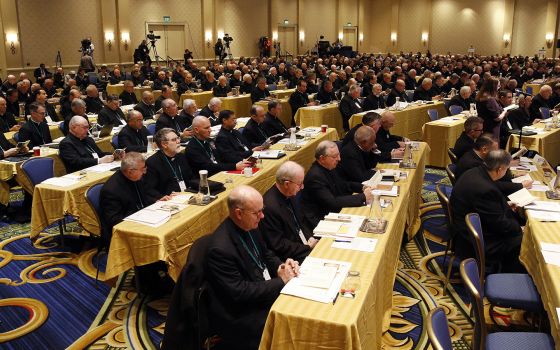

Bishops prepare to begin the general session meeting Nov. 14 in Baltimore. (CNS/Tennessee Register/Rick Musacchio)

This is how upside down and inside out things have become in the church: The U.S. bishops passed, by an overwhelming vote, a pastoral letter against racism during their recent meeting in Baltimore. Unfortunately, it was birthed in the shadow of the sex abuse crisis, discussion of which overwhelmed the conference meeting, and it will struggle to gain any notice amid the rubble of the ongoing fallout from the crisis.

It is a passable document and necessary, given the emergence of racism, xenophobia and anti-immigrant hate talk emanating not only from the corners of society but from the culture's corridors of power. It was one of the few items on the original agenda that wasn't scrubbed because of the need to discuss the abuse crisis.

In the current atmosphere, however, it felt like an afterthought, the discussion out of place. It was a statement of moral purpose by a group of men who have yet to find their collective moral core in dealing with the most perilous danger to the church in modern history.

Some blame the lack of action on the Vatican, which ordered the bishops to not vote on any of their proposals until after an international summit of bishops on the issue in February. It became apparent, however, in the discussion that did ensue about the proposals that the bishops were hardly of one mind about them. In fact, there is every possibility that, according to one line of thought, Pope Francis sought the delay because he considered the proposals so inadequate. If that is the case, he inadvertently may have spared the bishops from coming away empty handed of their own accord.

The culture of the Catholic clergy and the state of the episcopacy have come under intense scrutiny as a result of the crisis, especially as it has dragged on for more than three decades and spread through the global community. And neither the culture nor the leadership level of the church comes off looking good.

We've posted an open letter to the U.S. bishops saying: "There is nowhere left to hide." "It's over," we wrote. "All the manipulations and contortions of the past 33 years, all the attempts to deflect and equivocate — all of it has brought the church, but especially you, to this moment. It's over."

What's left to do is the only thing the bishops can't be forced to do, and that is the interior work familiar to all of us because of our shared sacramental tradition: a deep examination of how the culture got to the point where bishops could turn their backs on abused children to hide the guilty clerics. Confronting that question honestly will go a long way toward pointing the episcopacy in the direction of needed reforms.

Advertisement

In a panel discussion prior to the bishops' meeting, Fr. Clete Kiley, who once served as executive director of the committee on priestly life of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and as principal staff person in the late 1990s on what was then the ad hoc committee on sexual abuse, got to the heart of what's missing in the ongoing discussion of abuse. "I'm going to keep returning to this idea of [clerical] culture," he said, "because we haven't unpacked that enough. We've changed policies and procedures and, to some degree, they've been effective. But we did not really analyze culture."

That last is the most difficult bit and one that keeps escaping the bishops' agendas. Perhaps they will get to it in January when they're scheduled to go on retreat together in Chicago to reflect on the problem.

It is easy to take solace in what has been done to this point — and the bishops have done a lot, as Kiley points out. Psychologist Thomas Plante notes those procedural and structural changes and says they've contributed to the sharp decrease in the number of cases reported — "barely a trickle" — since 2002.

One of Plante's primary points about the recently stoked furor is that it is based on reporting of incidents that are decades old and that are repeated for effect by popular media. A certain amount of that critique is valuable — a lot of the recent reporting is just a regathering of old incidents and data. But the unraveling of previously unknown old incidents — and the bishops' complicity in a cover up of those crimes — will continue to roll out as diocese after diocese either voluntarily or under some form of grand jury subpoena release documents or unlock previously secret files.

Theologian and lawyer Cathleen Kaveny of Boston College, in that same panel discussion, said she believes there's been a kind of "paradigm shift" in how Catholics view the scandal. It once was perceived as the crimes of a small and disturbed group of clerics, but it became clear that the problem was widespread, not only in this country but throughout the globe with a similar narrative from country to country. As a result, Catholics began seeing it as a systemic problem of tolerated and accepted crime. And if that were the case, then a great many presumptions about who we are as Catholics and what the church and clergy mean are called into question.

The fate of the pastoral against racism — as an agenda item that couldn't be dumped but also could not be given the prominence or the robust discussion it deserves — is but the latest indicator of how off-the-rails we've gone as an institution. That condition was not going to be solved in a few days under the bright lights of public scrutiny. It will require a longer process. But to discover the bishops are still so far from discovering the right path back only adds to the flock's discouragement and bewilderment about their shepherds.