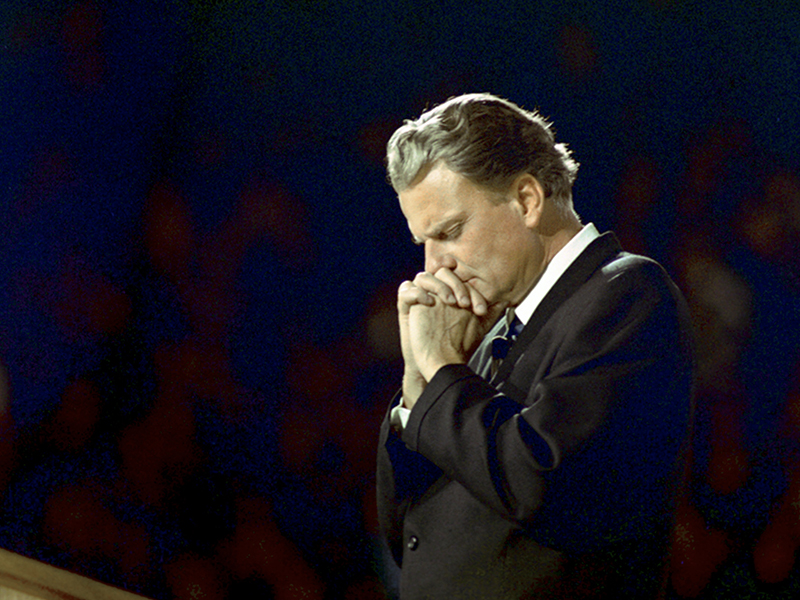

Billy Graham, photographed in Pittsburgh in 1968. (RNS/Photo courtesy of Billy Graham Evangelistic Association)

The Billy Graham I knew as a journalist was unfailingly kind, modest and helpful; a generous spirit endowed with striking personal gifts who, like many natural leaders, sometimes got in over his head. He was born with the instincts of a preacher in a culture that encouraged it. He embodied the hopes of post-Depression ordinary evangelicals who aspired to be "haves." In becoming famous, he was exposed to lures of patriotism and power that seemed to compromise his potential.

It was never clear to me whether Graham was a willing accomplice in the attempt by the religious right to use him to rally support to their cause. During an era of great social upheaval, he was for the most part subtly coopted by the likes of Richard Nixon to support a reactionary political agenda. Indirectly, mostly, by blessing it. When Nixon felt unable to go out to church, he assembled worship services in the White House with Graham’s approval. While he fostered the image of "presidential chaplain" by becoming available to a succession of presidents, his sympathies were clearly on the conservative side. At the same time, of course, he also continued to bring the Word to the masses, but the political part captured most media attention.

His implied political partisanship, while never overt, became in my estimation the prelude to a wave of blatant, Christian right solidarity starting with Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell. By comparison to those who followed him, Graham appeared to be a bystander, but by linking his reputation to certain causes he sent a clear signal.

Graham repeated the same sermon outline tirelessly and exuberantly over the continents. It was the bare-bones message that summoned sinners to be born again. Different examples of sinfulness were inserted to tap into current events, as were warnings of imminent dangers from worldly threats, but the narrative from dire straits to invitation to salvation remained the same, and Graham delivered it in masterly fashion. It was a vintage American form which had its own rightful place in the nation’s history.

The unfortunate consequence of Graham’s pungent appeal was that it instilled a widespread view of the Gospel that obscured its greatest challenge, the emerging conviction that the Bible had been shown by scholars to be full of human error and rewriting. This historical-critical outlook, espoused by the mainline Protestants like Presbyterians and Methodists, was flatly rejected by Graham’s origins in biblical infallibility. Graham might have offered his good offices to invite dialogue in search of a degree of reconciliation, but he was already regarded skeptically by unbending fundamentalists to further risk his own standing with them – and didn’t fancy taking on such knotty theological issues.

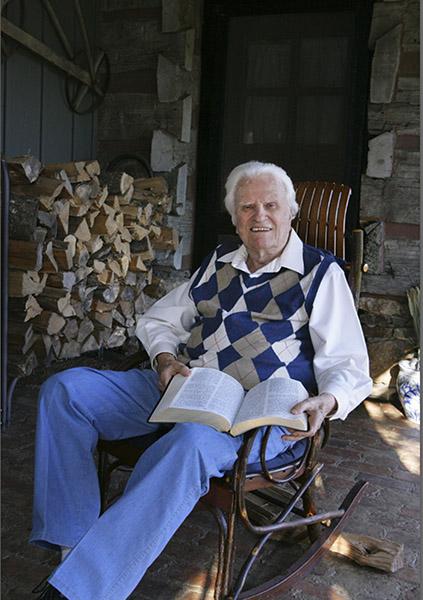

Rev. Billy Graham, famed preacher who was best known for his televised evangelism broadcasts, died Feb. 21 at his home in North Carolina at age 99. He is pictured at his home in 2010. (CNS/Billy Graham Evangelistic Association handout via Reuters)

Graham’s inherent modesty kept his self-image impressively edited. He would openly allow that he wasn’t a theologian or a scholar. I once asked him if he had had doubts about his faith since his own conversion. "Never," he said quietly and earnestly.

He did open doors to non-evangelical churches and broke the color line in his crusades, though remaining silent on matters of racial policy and the ethics of war. So far as the public knew, he saw no reason to employ the Bible’s lessons to strife over social justice.

Graham’s moral authority was exercised on behalf of a relatively few principles of personal morality spelled out in the Ten Commandments and related sources. The morals he preached were those borne by traditional evangelicalism and, as such, were limited by the need to complement the responsibility for personal behavior. There was virtually no allowance for "social sin" like racism and sexism that was being emphasized by liberal churches.

Graham, then, inadvertently helped promote what was then a minority movement in Protestantism as standard-brand Christianity, not from any evident animosity toward mainline churches but partially as a result of an inability or unwillingness as a recognized leader to narrow a widening gulf among churches.

The irony was that Graham sometimes served as a prop for opportunists who revered his talents as a persuader but had no use for his message. As a trusted public figure, therefore, Graham was proposing a morality that Americans were increasingly wont to ignore but with power and appeal to a public that craved an old, if fading, ideal of exceptionalism.

He held fast to those core values in his life as a big-fishbowl preacher and leader, and his domestic life as husband of a talented woman and father of five spotlighted children. By and large, he fit the profile of the post-World War II professional man on the rise — a hardworking breadwinner who spent long hours at his job, leaving child-rearing and domestic chores to his wife, a father who had relatively little time with his kids, and a parent unable to dissuade them from the influence of drugs, drinking and other threats to evangelical sanctity.

His failings could be ameliorated by his capacity to confess wrongs such as slighting Jews, cozying up too much to the Vietnam war machine and ignoring Watergate. His tendency toward upward mobility (always in the guise of pastoral concern) at times led him to hobnob without ethical spectacles, but he could apologize.

Advertisement

With perhaps similar innocence, Billy Graham arguably did help facilitate the rise of evangelicals in the social and economic class structure. The question is how much his own longing to be accepted by the established class affected his religious calling. He didn’t show a taste for lavish living or chest-thumping. To the contrary. His growing evangelical association was the cleanest, sparest I’ve ever examined. When his alma mater, Wheaton College, wanted to place his name on a museum dedicated to his evangelism, he rejected the invitation for years before relenting.

One Sunday long ago, Graham and I appeared on an edition of "Meet the Press." Afterward, he offered me and my 5-year-old son a ride to the airport. As we alighted from the car, he pulled an Irish wool hat down as far as it would go on his head. He kept it on tight during the flight. We chatted but he did his best to remain inconspicuous. My son, having listened to chatter about him at the studio, once or twice called him "Billy," causing me to cringe but evoking delighted smiles from Graham. He was a gracious man who was catapulted onto a stage which had never before existed – and stood tall even when he came up short.

[Ken Briggs reported on religion for Newsday and The New York Times, has contributed articles to many publications, written four books and is an instructor at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennslyvania. His latest book is The Invisible Bestseller: Searching for the Bible in America.]

*This appreciation was updated at 3:40 p.m. CST, February 23, 2018.