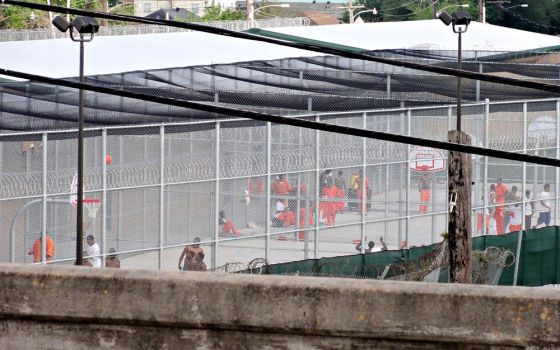

The yard of Orleans Parish Prison in New Orleans is seen from the overpass of what was then Jefferson Davis Parkway in 2012. Last year, the parkway was renamed for Norman Francis, former president of Xavier University of Louisiana, a Catholic historically Black university. (Flickr/Bart Everson)

Editor's note: A year ago, after the murder of George Floyd, the U.S. exploded with protests bringing attention to the scourge of police violence against African Americans. Initial calls to "defund the police" have since been nuanced to call for substantive reform that includes reappropriation of funds for other social services. But policing is just part of a massive justice system that includes courts, jails and prisons. In this four-day series, "Justice Reimagined," two NCR writers look at the prison abolition and reform movements, as well as what might work better: restorative justice. The three stories on prison abolition/reform are by Bertelsen fellow Madeleine Davison; former NCR executive editor Tom Roberts reported the two pieces on restorative justice.

Previous stories in the series:

Prison abolition is not a new term. But in the year since the police killing of George Floyd, uprisings for racial justice and against police brutality have galvanized people across the United States to ask: Are police and prisons really necessary?

For some of these abolition activists, the desire to abolish police and prisons comes from their Christian faith and a belief that no one is disposable.

Some Catholic advocates who spoke with NCR said their inspiration for working toward prison abolition comes from the Catholic social teaching concept of preferential option for the poor and marginalized. And of course one of the seven corporal works of mercy is to visit prisoners.

Dwayne David Paul (NCR screenshot)

Policing and prisons have long been used against Black people and other marginalized groups, said Dwayne David Paul, a Catholic educator and writer who works for the Collaborative Center for Justice but spoke to NCR in his capacity as a private individual.

"Social teaching ... says we shouldn't have things that harm the most vulnerable," Paul said. "And empirically and historically, [prisons and police] are institutions that do just that. Then we shouldn't have those institutions."

Syrita Steib, executive director of Operation Restoration, which supports currently and formerly incarcerated women, said her faith in God and her experience as a formerly incarcerated person tell her to give people opportunities to change. Steib spoke recently at an online panel hosted by the Georgetown University Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life.

Dean Dettloff, a lecturer at the Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto, said liberation theology also points the way toward abolition.

"Liberation theology draws us into an understanding of our faith that is in solidarity with the prisoner first, more than, let's say, the prison guard," said Dettloff, who is Catholic.

Dettloff pointed to a recent report published by the Prison Ministry Office of the Bishops' Conference of Brazil detailing horrific conditions in Brazil's prisons.

"Abolishing prisons is the first step toward freedom, which is a constant struggle," said the ministry's report, citing abolitionist scholar and activist Angela Davis.

The Rev. Nikia Smith Robert, author of "Penitence, Plantation and the Penitentiary: A Liberation Theology for Lockdown America" and founder of Abolitionist Sanctuary, said womanist virtue ethics — an anti-oppression and constructive theological framework based on the work of Black women religious scholars, particularly author and ethicist Katie Geneva Cannon — informs her belief that the criminal legal system punishes Black women for actions that come from a place of love, courage and virtue under an oppressive system.

The Rev. Nikia Smith Robert (Courtesy of Nikia Smith Robert)

For instance, Smith Robert's mother, a Black working-class single parent, sometimes had to forge doctor's notes so she could get off work to take care of her kids during school holidays, or alter rent documents so she could afford to pay for housing amid gentrification and skyrocketing costs.

"Whereas society may see 'criminal' in my mother's actions, what I saw were values of ingenuity. … I saw courage, [and] some of the virtues we see in other canonical ethical systems," Smith Roberts said.

She said that her contribution to womanist virtue ethics requires centering Black women's experience with carcerality, working to "abolish the carceral state" and to transform the oppressive conditions that create a need for unlawful actions of survival in the first place.

"How do we repair and revisit those structural injustices, so that everyone has access to the resources they need to survive ... to meet their basic needs, and ultimately to self-actualize and thrive?" Smith Robert said.

Although some early prison reformers tried to emphasize penitence and rehabilitation, Christians also have been complicit in promoting a theology of punishment and supporting incarceration, said Vincent Lloyd, director of Africana Studies at Villanova University and co-author with Joshua Dubler of Break Every Yoke: Religion, Justice and the Abolition of Prisons.

Quakers influenced a model of prisons that emphasized penitence through solitary confinement, while Puritans believed in the power of forced labor to rehabilitate people, according to the Journal of Ecumenical Studies.

"In practice, it also leads to breaking apart communities and doing psychological damage to people who are being isolated," Lloyd said. "And the focus on punishment or correction rather than formation can pull people away from growth together in a flourishing community."

Advertisement

Many modern churches push punitive ideologies and respectability politics that harm incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, Smith Robert said.

"Christians have contributed, in various ways, both very specifically and materially to creating a kind of cultural atmosphere where punishment and correction are valued in the U.S. prison system," Lloyd said.

Still, he said, Christians can breathe moral energy into the abolition movement. Christians who supported abolishing slavery often referred to it as an "abomination" and argued against it on moral and religious grounds, Lloyd said.

The image of a person in shackles or in a cage is part of the same paradigm as slavery and Jim Crow, Lloyd said. All three of these institutions damage "the image of God in the human," he said.

An incarcerated woman sings during a Mass on Dec. 19, 2019, at the Suffolk County Correctional Facility in Yaphank, New York. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

"If the image of God is in the human, and that image is being stamped out, or distorted ... then all the people and systems that are involved in that kind of work are morally culpable," Lloyd said. "And we have an obligation to organize against them."

There are a number of ways Christians can get involved in the fight to end incarceration. Smith Robert, who runs Reverend Daughter Ministries, said in an email to NCR that she works with churches to analyze their own sermons and practices and help them become what she called an "abolitionist sanctuary" that centers Black women and others impacted by the criminal legal system.

Hannah Bowman, creator of a website called Christians for the Abolition of Prisons, which offers educational resources on mass incarceration and abolition, said she recommends that people who want to get involved but who have not been personally impacted by the prison-industrial complex reach out to abolitionist organizations* and sign up to exchange letters with an incarcerated person.

David Brazil, co-founder of the group Abolition Apostles, said becoming pen pals with people in prison has helped him develop strong friendships and connect with people who are relatively isolated from society. It has also helped him learn about the inner workings of the prison system and connect his friends inside with other resources, like books and funds for reentry.

"Were I in that circumstance, I would want somebody to reach out to me," Brazil said. "So that's just how you love your neighbor as yourself."

Abolition also involves creating new kinds of relationships with one another — relationships that are based on mutual support and growth, rather than on isolation and punishment, advocates told NCR.

"Abolition is about more than just abolishing prisons, it's about abolishing a society that would create prisons," Dettloff said. "[It's about] abolishing the kinds of dysfunctional relationships that would lead us to think that putting someone in a horrific place like the prison is a reasonable thing to do when a relationship fails, or when a violence is done."

*This article has been edited to correct Bowman's recommendation.