Jeanne Bishop (Courtesy of Jeanne Bishop)

Editor's note: A year ago, after the murder of George Floyd, the U.S. exploded with protests bringing attention to the scourge of police violence against African Americans. Initial calls to "defund the police" have since been nuanced to call for substantive reform that includes reappropriation of funds for other social services. But policing is just part of a massive justice system that includes courts, jails and prisons. In this four-day series, "Justice Reimagined," two NCR writers look at the prison abolition and reform movements, as well as what might work better: restorative justice. The three stories on prison abolition/reform are by Bertelsen fellow Madeleine Davison; former NCR executive editor Tom Roberts reported the two pieces on restorative justice.

Previous stories in the series:

Of the infinite ways in which Jeanne Bishop could have reacted in the wake of that shattering phone call, the one that came the day after a family dinner to celebrate her sister's pregnancy, the one that essentially announced that all the reasons for celebration had been turned to horror and grieving, she permitted only one to dominate, and it surfaced almost immediately: "I don't want to hate anyone."

Her life was ripped from its moorings on a Palm Sunday morning, when she was already in choir robes, palms in hand, just before the start of a service at Fourth Presbyterian Church of Chicago. She was summoned to take the call from her father, who said: "Nancy and Richard have been killed."

Her sister, Nancy, and brother-in-law, Richard Langert, had returned to their townhouse in Winnetka, Illinois, after leaving the dinner with Jeanne and her mother and father. When they arrived, a teenage gunman, David Biro, then only a junior in high school, was sitting in the living room, waiting. After a brief exchange he handcuffed Richard, ordered the couple to the basement where he shot Richard in the back of the head and fired three shots into Nancy's side and stomach. Richard died instantly, Nancy lived, it is estimated, for about 15 minutes after the killer fled, enough time to crawl across the floor nearer to her dead husband and draw on the floor in her own blood a heart and the letter 'U'.

What followed is detailed in a compelling narrative of life-changing heartbreak and healing in her first book, "Change of Heart: Justice, Mercy, and Making Peace with My Sister's Killer."

Bishop is a lawyer, one who left a big firm and big salary to become a public defender after her sister and brother-in-law were killed. She is also a writer and a believer of deep faith and conviction. She gives a great deal of credit to God for the journey she undertook and the results of that journey to date, described over the arc of two books.

But the story is as much about cooperation with grace and acting out of a faith that doesn't first demand certainty as it is a story of God's action in a life. And it involved at the time a lot of anguished questioning of that same God.

Her personal experience also gave her a unique authority when she began to investigate the remarkable friendship that developed between Bud Welch, a gas station owner in Oklahoma City, and Bill McVeigh, an auto parts worker from western New York, two working class Catholics whose meeting resulted from horrifying circumstances.

Welch's daughter, Julie, was 23 and just beginning to engage life as a vibrant young adult when she was killed in the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. McVeigh's son, Timothy, then 26, was the mastermind behind the terrorist bombing of that building. He was later executed, an outcome he desired, by the federal government.

Bishop recounts the path from the pits of despair and hatred on the part of Welch to what today she terms "enduring" friendship in Grace from the Rubble: Two Fathers' Road to Reconciliation After the Oklahoma City Bombing. The book received a 2021 Christopher Award.

Bishop said her reaction to the murder of her sister and brother-in-law, the determination not to hate, startled even her. The statement emerged in a conversation at the police station soon after the killing. It surfaced, she writes, because "I grasped at that moment that evil had intruded into our lives. I could not ignore it. It was too vast and terrible not to change me. It required a response."

A response of hatred, she reasoned, "would take me away from who Nancy was, someone who loved, and move me closer to who the killer was, someone who could snuff out the life of another human being with the squeeze of a trigger. Whoever he was, I would not hate him."

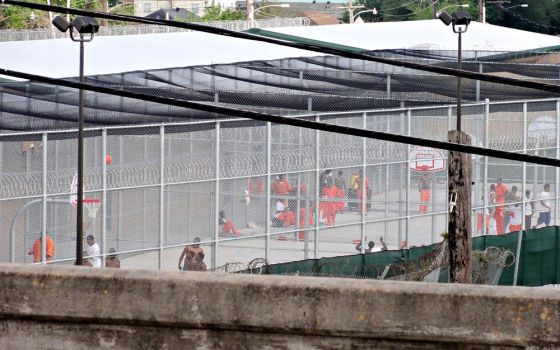

David Biro at Pontiac Correctional Center in Pontiac, Ill., in 2013 (Newscom/Chicago Tribune/Nancy Stone)

If that conviction came early on, it was hardly determinative of the next steps and the steps beyond that. It took more than 20 years for Bishop to reach the resolve that resulted in a letter to Biro in prison that ultimately led to their meeting. She is still advocating for a reduction in sentence, convinced that minors should not receive life without parole, the sentence Biro received.

"One of the boards I'm on is this group called Restore Justice Illinois and we're trying to eliminate life without parole for juveniles and anything that creates these long, long sentences for young people," she said in a recent phone interview.

She said two other board members had visited Germany to learn about that country's system. She described it as different from the warehousing that goes on in the United States.

"One of the first people you meet is your re-entry counselor," someone who works with you "to make sure when you get out of prison two, three, four, 10 years later, that you have had counseling, that you have job skills, that you're ready to deploy out in the world to support yourself."

A similar question about hate occurred to Welch, who began drinking heavily and regularly visiting the site of the Oklahoma City bombing after his daughter's death. Bishop writes in Grace from the Rubble that he was "asking myself a lot of questions. What do you do to get rid of this terrible hate?" He wondered if McVeigh's execution would aid the healing process, a question that he pondered for about a month.

Bud Welch, a Catholic layman, speaks about his daughter, Julie, who was killed in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Welch opposed the death penalty for bomber Timothy McVeigh. He speaks March 21, 2005, at a press conference in Washington at which the U.S. bishops launched a new initiative to end use of the death penalty. (CNS/Paul Haring)

According to Bishop's account in her book, Welch then spoke to an AP reporter who asked if he'd be glad when the execution occurred. Welch responded, "No, that's not what I want." The quote hit the wires and he became an instant target for news outlets everywhere. His response to the unbelieving inquiries: "When I was for the death penalty for Tim McVeigh, I was wanting to do the same thing he had done. It just made no sense to me."

He told another outlet that the vengeance and rage of the sort that led to the bombing "has to stop somewhere."

In the telling of her own tale and that of Welch and McVeigh, Bishop has become a high-profile advocate for the restorative justice process and for reform of the justice system. In a keynote address she gave during a 2019 conference on the subject sponsored by University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis, she asked why the "dream" of restorative justice matters.

"It matters because we have to learn how to respond to evil because there's been no shortage of evil since [the Oklahoma City bombing]. We've had Newtown and Parkland and El Paso and Dayton and Tree of Life Synagogue and Mother Emmanuel Baptist Church in Charleston. And we know that we have to respond, and if our response is hatred and vengeance, that will get us nowhere. It will just cause more bloodshed."

She recounted the chilling calculation McVeigh described to journalists before he died: "He said, 'You know they think they've got me, I'm some kind of trophy, that with the death penalty they've won. They haven't won. By the crudest terms: 168 to 1.' And we know what he meant by that."

Advertisement

The conclusions she reaches about restorative justice, the ones on display today in talks and conferences and panel discussions, might be admirable or cause astounded heads to shake, but the work required to get to these end points is essential. It is, some might say, the destination without end. During this past year of COVID-19-inspired cleaning, said Bishop, she has come upon her journals from the earliest days of that work. They were written largely during a family getaway to a friend's house on Sanibel Island where they went to spend some time grieving and healing.

In the immediate aftermath, her meditations were angry confrontations with God, with big questions about whether God even existed. "I was pouring my heart out in this journal. It was my cry of agony and rage at God," she writes in her book.

She said she "was never going to be the person who wrote the book, 'Nine Easy Steps to Forgiveness.' I don't believe that's how it happens or that it's even appropriate."

But she's considering revisiting the journals as the heart of a story about how her argument with God turned out.