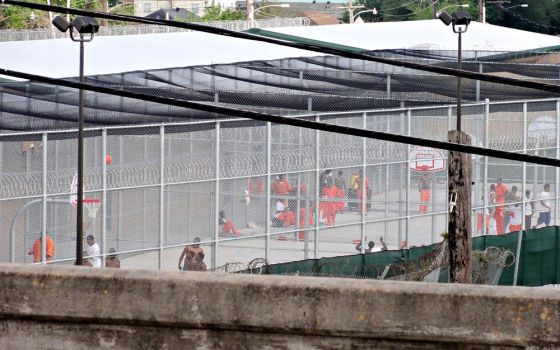

A priest prays with a death-row inmate in 2008 at Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Indiana. One in five prisoners in the world is in a U.S. prison. (CNS/Tim Hunt, Northwest Indiana Catholic)

Editor's note: A year ago, after the murder of George Floyd, the U.S. exploded with protests bringing attention to the scourge of police violence against African Americans. Initial calls to "defund the police" have since been nuanced to call for substantive reform that includes reappropriation of funds for other social services. But policing is just part of a massive justice system that includes courts, jails and prisons. In this four-day series, "Justice Reimagined," two NCR writers look at the prison abolition and reform movements, as well as what might work better: restorative justice. The three stories on prison abolition/reform are by Bertelsen fellow Madeleine Davison; former NCR executive editor Tom Roberts reported the two pieces on restorative justice.

Previous stories in the series:

It would make perfect sense were the two men perpetual enemies. One lost a 23-year-old daughter in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. The other lost a son, executed by the federal government, for setting off the truck bomb that killed 168 people in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.

But Bud Welch, who lost his daughter, Julie, in that horrible act of terrorism, and Bill McVeigh, whose 26-year-old son Timothy masterminded the slaughter, have become "enduring friends."

Their story is told by lawyer and author Jeanne Bishop, whose book, Grace from the Rubble: Two Fathers' Road to Reconciliation After the Oklahoma City Bombing (Zondervan, 2020), recounts the unlikely bond that developed between the two men. (See NCR's accompanying interview with Bishop here.)

In a 2019 keynote speech, she said the relationship between the two fathers exemplified restorative justice, the theme of the conference sponsored by the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis. "It looks like two people sitting down together and talking, and understanding one another."

In the end, that is the distilled truth of it. Their tale — and her own story — however, would show that the path to that kind of understanding takes time and can't be the product of some judicial mandate. The results, though, even among the less notorious, can be just as joltingly unexpected and rewarding.

***

Restorative justice.

It is the second word with which we are most familiar. Longstanding philosophical debates aside, we, in the context of contemporary western culture, don't have to struggle for the meaning.

Justice has to do with impartiality, the formal application of fair play and deserved punishment. There's a system named for it with clear expectations of how it works.

Its administration is objective, emotionless, blind.

Restorative, as modifier, tugs justice in new directions, toward the messiness of human experience and emotion, toward the imprecision of consequences. It leads into the tangled calculations of harm done, not just to the victims of crime, but also to the perpetrators and beyond, to family members, friends, the community. It dares to consider the growing body of research on the devastating and lingering effects of trauma on individuals.

Those two words seem of growing importance for at least two reasons. They crop up with increasing frequency in a range of circumstances, and they appear to present a paradox of biblical proportion and one terribly out of sync with the transactional nature of this era.

Use of the "RJ" concepts in schools, for instance, is growing as an alternative to traditional approaches to discipline.

Google the two words and discover websites addressing the growth of the concept. You'll find panel discussions and speakers of all sorts addressing the possibilities, as well as news of initiatives taking hold in a wide range of institutional settings. That is especially true of Catholic groups and institutions.

In an interview with NCR, Krisanne Vaillancourt Murphy, executive director of the Catholic Mobilizing Network, which advocates abolition of the death penalty, said part of the task her organization has taken on is to "demystify" or "clarify" what restorative justice means. People may have heard of restorative justice and think "it certainly sounds like a good thing," she said, but they don't know really what it is. "So we've been trying to lift up those stories where people have been using restorative practices, where there's clear restorative approaches."

Her organization was the lead sponsor of a major several-day virtual conference last October, titled "Harm, Healing, and Human Dignity." The conference was done in collaboration with San Diego University and the Diocese of San Diego.

Panelists and speakers — including death penalty abolitionist Sr. Helen Prejean and Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle of Los Angeles, founder of Homeboy Industries, a gang-intervention organization — exemplified the range of situations in which the restorative justice approach is used. A common thread in the stories is how the restorative justice approach has brought offenders — from gang members to drug dealers to white collar criminals — to an honest accounting of the harm they've done and, at the same time, guided them to a restoration of their lives.

Restorative justice goes deeper than the exchange of punishment for wrong; it involves a search for understanding. Retribution, the normal application of justice — fines, jail terms, payment for damages — is just the beginning of the tale.

Justice standing alone may be swift; restorative justice operates in the long haul. Setting up meetings between the convicted and their victims, for instance, can take months. A variety of in-prison restorative justice programs work on a voluntary basis and require acknowledgement on the part of participants of the harm they've done and agreement of victims to participate.

Fr. Larry Dowling, one of the panelists, is pastor of St. Agatha Parish in Chicago's North Lawndale area, which he describes as having been deeply affected by systemic racism. He said the parish makes use of restorative justice practices in the elementary school setting and in dealing with domestic and community violence and tensions within families.

"We do circles, just bringing parents together and youth with parents," in "dealing with physical and verbal violence." Two people "from the streets" who have turned their lives around now go into prisons regularly to work with incarcerated men teaching parenting, life and "manhood" skills. When those men are released, he said, the parish works with other community organizations to reintegrate those individuals into the community.

The parish also works with an official Restorative Justice Community Court of Cook County, which allows anyone ages 18-26 charged with a nonviolent felony or misdemeanor and who has a nonviolent past, to engage in a process that potentially leads to dropped charges and an expunged record.

Justice is a verdict rendered by a system with tight boundaries and rules for what can and cannot be considered. Restorative justice undoes the blindfold to take account of all the harm done on all sides of the ledger and dares to ask: What next?

The possibilities, however, can overwhelm easy definitions and expectations, according to lawyer and author Bishop.

"The term 'restorative justice' may promise too much — that we can have both restoration and justice," Bishop writes toward the end of her first book, Change of Heart: Justice, Mercy, and Making Peace with My Sister's Killer, a recounting of her decadeslong struggle to deal with the shooting death of her pregnant sister and her husband in their home by a teenage intruder. It took Bishop decades to arrive at a face-to-face meeting with their convicted killer.

The implied question in that statement — Does restorative justice promise too much? — is not idle speculation, nor is it a conclusion. It is more an acknowledgement that the elements constituting restoration don't bend easily to legal structures. Grace, she continues, "is essential to get to restoration … a path that is harder and steeper and truer to the cross." Maybe, she concludes, "it is restorative mercy we must seek."

***

While the concept of restorative justice, applied within the justice system and elsewhere, doesn't rely on religious language, its principles emerge from the practices of Indigenous cultures and the wisdom of major religious traditions, Christianity certainly among them. Healing circles, disciplined dialogue among offenders and victims, examination of spiritual as well as physical and material harm are incorporated into the process.

Within that larger reality is an expanding Catholic universe. At its center are key well-known and longtime practitioners of the process such as Prejean and Boyle, whose fundamental conviction — that no one is defined by the worst thing they've done — is a foundational tenet of restorative justice.

Mention the term in Catholic circles and invariably the work of former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Janine Geske will surface.

She became intrigued with the prospects of restorative justice while still on the sentencing side of the bench. After considerable deliberation, she decided to leave the court and in 1998 returned to teach at Marquette University Law School, from which she had graduated. There, she explained in a 2006 essay, she proceeded to "transform future lawyers by exposing them to issues of poverty and violence and then teaching them how to become servant leaders in their legal careers."

Advertisement

That point of view did not emerge fully formed in an instant. Geske credits her Catholicism and a broad spiritual search, as well as her long involvement, while a judge, educating inmates about the justice system, with leading her to restorative justice.

If there is no tidy definition, there is a term central to the concept of restorative justice that separates it from simple punishment or rehabilitation programs, essential as they may be. The word is harm — the harm done to both victim and perpetrator, to family members and friends on both sides of the equation, to the community beyond.

"Harm is not only defined by something that's criminal," said Geske in a recent interview with NCR. "Something criminal is just something some legislative body has decided to attach punishment to. But many harms we have in society are much worse than many crimes. I would say a breach of a personal relationship, a betrayal of somebody, is a lot more harmful than someone stealing something out of your front yard," she said.

Like so many others who have become advocates of the process, Geske approached restorative justice with skepticism, not only because it steps out of the clear bounds of retributive justice, but also because she feared retraumatizing victims by revisiting the harm that was done.

"I was sitting in homicide and sexual assault court trying these cases nonstop and people were talking about restorative justice. I had this vague idea about what it was. And the idea that I would ever put a survivor of a sexual assault or a family member of a homicide victim across the table from the perpetrator was just, you know, cuckoo, just nuts to me."

Fr. Daniel Griffith, left, and Hank Shea, right, are pictured with Janine Geske, a former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice. (Mark Brown/University of St. Thomas)

She went from thinking restorative justice a "pretty crazy and some liberal kind of nutty idea" to learning that "in walking with people into these experiences that there's something much bigger. And for me it is an attachment to God and God's presence in this process." In the normal course of her work, she doesn't use such religious language, she said.

Geske, beginning with her work early on at Marquette University Law School, has raised the profile of restorative justice far and wide over decades. One of the most significant effects of her tutelage, however, can be seen at the University of St. Thomas School of Law and a class taught by the lawyer team of Hank Shea, a former federal prosecutor, and Fr. Daniel Griffith, who was a lawyer before becoming a priest.

Shea, who specialized in prosecuting white-collar crime, is School of Law Senior Distinguished Fellow and Fellow of the Holloran Center at St. Thomas. Griffith is both Wenger Family Fellow of Law at St. Thomas and pastor of Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church in Minneapolis. He is also the liaison for restorative justice and healing for the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. The two regularly refer to Geske as a mentor.

In opening the 2019 conference on restorative justice at the University of St. Thomas School of Law, Shea advised: "Put aside most people's traditional notions of punishment … giving the wrongdoer what he or she deserves. Put that aside and open up your minds and your hearts to a different way of looking at how we should deal with wrongdoing in our society."

That is unusual talk from a former prosecutor, and while there is an abiding religious conviction attached to Shea's understanding, he argues most convincingly for the practicality of this "different way." Both he and Griffith point to the current justice system and conclude: It doesn't work well.

The United States is clearly an outlier when it comes to rates of incarceration. One in five prisoners in the world is in a U.S. prison. The United States heads the list (immediately followed by China) of countries in terms of the total number of people incarcerated and the percentage of population incarcerated.

"What kind of society keeps making the same mistake over and over again by incarcerating people without trying to change them?" asked Shea. "And we've been doing that for generations."

New York City police place a demonstrator in plastic handcuffs Nov. 1, 2020. (CNS/Eduardo Munoz, Reuters)

The futility is obvious, he said. "If you don't get to the core of what caused them to do it, which is what restorative practices do, you're never going to fundamentally change their behavior. They're going to do it again and hurt more people."

Griffith is the one who convinced Shea to include restorative justice in his popular Crime and Punishment course. Next year, they said in a recent joint interview with NCR, they intend to include a greater emphasis on racial justice, which has particular relevance for a law school in a city that was site of the recent George Floyd murder trial.

Griffith agrees with the sheer pragmatism of the approach in terms of results. But there's another angle, biblical, that he sees in the process. He describes restorative justice as coming out of the heart of the Christian Gospel and the Catholic tradition.

Bishop Robert McElroy of the Diocese of San Diego would agree. In a talk introducing the Catholic Mobilizing Network's conference last fall, McElroy reflected on Pope Francis's encyclical Fratelli Tutti, and the deep connection between its expression of Catholic social teaching and the concept of restorative justice.

"Restorative justice," said McElroy, "is more expansive and demanding a notion of justice than procedural justice can ever hope to be." Its possibilities also extend into every area of life, he said. "The beauty of the ethic of restorative justice is precisely that it breaks through the false order of the justice system as it currently exists in our country, our church, and our institutional life."

"Another word that occurs to me from our tradition is 'incarnational,' " said Griffith. It's true gospel because it's incarnational. If Christ enters into our humanity, into our suffering, in a way that's real, that's filled with meaning and restoration, that's really what restorative justice is," he said.

That incarnational breakthrough can be powerful enough to draw two working-class Catholic fathers grieving their dead children — one a terrorist, the other his victim — into an enduring friendship.