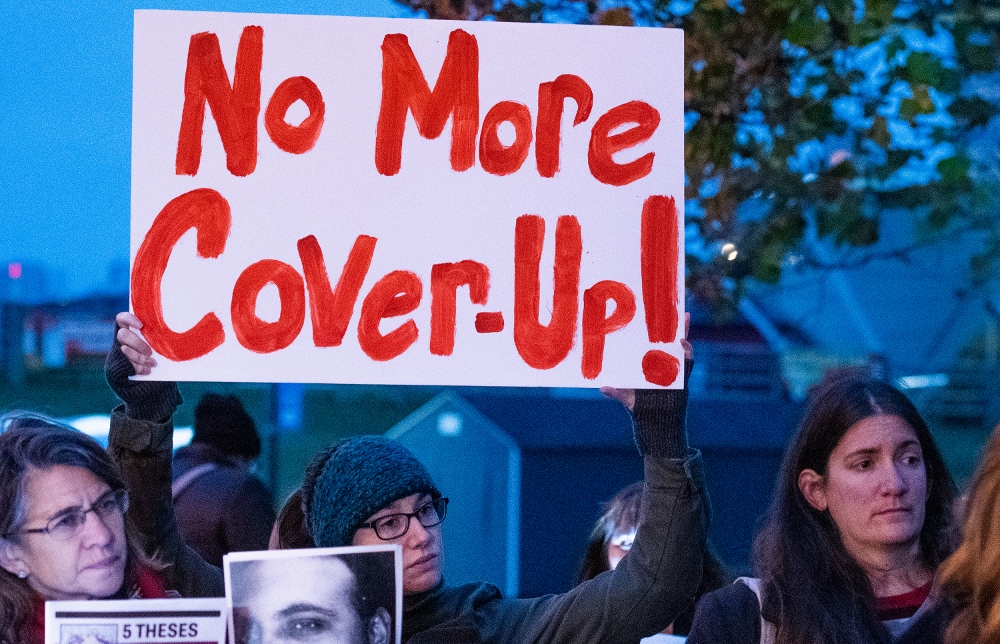

Suzanne Emerson, from Silver Spring, Maryland, holds a sign during a Nov. 12 press conference held by the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) as the U.S. bishops meet in Baltimore. (CNS/Catholic Review/Kevin J. Parks)

Speculation can be fun. But it's not helpful, at least not in the short run. And few would dispute that the U.S. church can't afford the luxury of "taking the long view" when it comes to the safety of kids right about now.

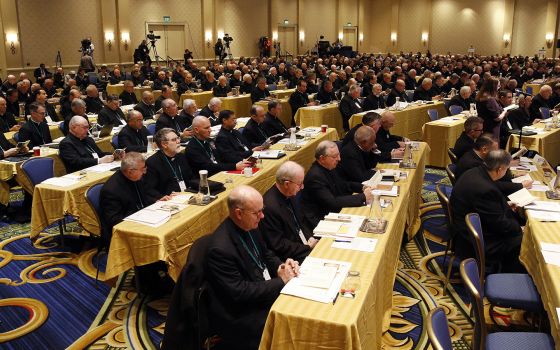

So let's stop guessing why Vatican officials nixed the nearly meaningless measures U.S. bishops had planned to discuss this week in Baltimore.

Instead, let's get practical and ask: What should U.S. bishops do now to protect kids, expose wrongdoers and heal the wounded?

The answer is actually fairly straightforward. Bishops must use their already vast powers to help stop more abuse and cover-up.

Let's start with two steps that are already being done across many U.S. dioceses sporadically but should be expanded, steps that do not require Vatican approval or new U.S. church policies:

- Every bishop should permanently and prominently post all names of proven, admitted and credibly accused clerics in the next two weeks (whether dead or alive, diocesan or religious order, lay or ordained, incardinated or not, given faculties or not, assaulted adults or kids). About 50 prelates have released such lists, going back to 2002. None of them has rescinded or regretted this common-sense safety step. No one in Rome has tried to stop these lists from being released.

- Every bishop should review his own diocese's abuse records, in case an old case has been overlooked or needs re-evaluation. Again, no bishop needs some Vatican bureaucrat to OK this process.

Advertisement

Then there are solid, practical but unprecedented steps that could be taken. Here are three:

- Every bishop should publicly denounce at least the worst enablers — those who ignored or hid abuse reports, those who knew of or suspected abuse but kept silent or acted deceitfully. Bishop Richard Malone of Buffalo, New York, leaps to mind, but there are many others.

- Every bishop should fire enablers — or at least publicly expose them — in his own diocese. Reams of depositions, news accounts, courtroom testimony — plus every bishop's own personal knowledge — point to hundreds of such individuals across the nation. I firmly believe there's at least one still on the payroll in every single diocese. They should be outed and ousted. Or, at a bare minimum, they should be demoted, disciplined and denounced.

- Every bishop should lobby for, not against, elimination of statutes of limitations and the creation of civil windows. Few would argue that kids are safer when predator and enablers can evade legal accountability by exploiting technicalities. Few would argue that victims heal better when they're denied a chance to prevent child sex crimes by shining a light, in a court of law, on wrongdoers.

Let's name names. Here are a few U.S. bishops who have taken positive individual steps forward just recently.

Bishop Stephen Biegler of Cheyenne, Wyoming, has publicly re-opened a probe into one of his predecessors, Bishop Joseph Hart, who faces about 10 accusers in his hometown of Kansas City, Missouri.

Last week, Bishop Shawn McKnight of Jefferson City, Missouri, insisted that religious orders disclose the names of their accused priests. If they refuse, McKnight says he won't let their clerics work in his diocese.

Also last week, church officials in Washington, D.C., put a pastor, Franciscan Fr. Moises Villalta, on leave for failing to "follow appropriate protocols related to reporting claims." He's one of just a handful of church employees to experience consequences for possibly violating the Dallas Charter. (Hundreds of current and former church staff should have long ago been suspended or worse for such violations.)

And this week, Chicago Cardinal Blase Cupich is pushing to move next June's U.S. bishops' conference meeting up to March, to enable quicker action. While such meetings have been largely ineffectual in the past concerning abuse, every one of Cupich's colleagues should jump on this suggestion.

(Sadly, at least one U.S. bishop is disingenuously using the Vatican delay to postpone a simple, proven prevention move taken by 50 of his colleagues. Bishop Peter Jugis of Charlotte, North Carolina, now says he'll delay his decision to reveal accused priests' names, though no one in Rome has ever stopped or tried to stop or even denounced a single prelate who has taken this common-sense step forward.)

I'm no canon lawyer. But I've been involved in this issue for three decades. I can confidently say that none of this requires Vatican approval or any kind of nationwide policy of any sort.

I agree wholeheartedly with those who say U.S. bishops should follow the lead of Chilean bishops and offer their resignations, en masse, to the pope. But while many Catholics, and U.S. citizens as a whole, would feel good about such a gesture, it too would not make a tangible difference.

Let's not let U.S. bishops off the hook because of what the Vatican has done. Rome's delay, in fact, could be a blessing in disguise if it forces U.S. prelates to look inward and do what they can do — and should have done long ago — to end and deter more crimes and cover-ups.

[David Clohessy is a St. Louis volunteer director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) and ex-national director of SNAP.]