Pope Francis arrives to lead a Mass for the Jubilee for Priests at St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican on June 3, 2016. (Photo courtesy of Reuters/Alessandro Bianchi)

In response to requests from bishops all over the world, on Sept. 9 Pope Francis gave more authority to national bishops’ conferences in determining liturgical translations and adaptations. He did this in a letter entitled "Magnum Principium" or "The Great Principle."

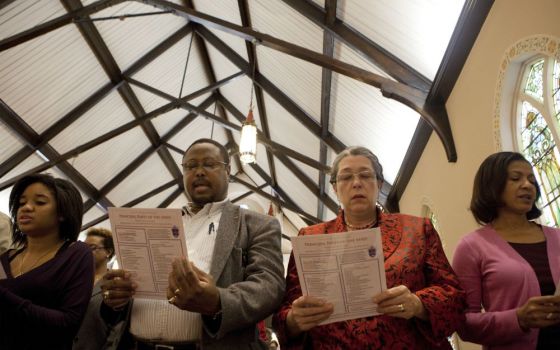

The reform of the liturgy was the most visible effect of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), which assembled all the Catholic bishops of the world to update the church. In their 1963 Constitution on the Liturgy, the council fathers recognized the need to encourage lay participation and to adapt the liturgy to local cultures. They had anticipated that most of this work would be done by national assemblies of bishops known as bishops’ conferences.

A provisional Mass, which I will call Liturgical Reform 1.0, was rolled out in 1965. This version called for translating the Mass into the vernacular and turning the altar around to face the people.

Liturgical Reform 1.0 was a revolutionary change, like moving from DOS to Windows. Further upgrades and fixes were anticipated. Ultimately, they resulted in the Mass announced by the pope on April 28, 1969, which I will call version 2.0. This upgrade included significant revisions in the introductory rite, the presentation of gifts, the kiss of peace, and additional Eucharistic prayers.

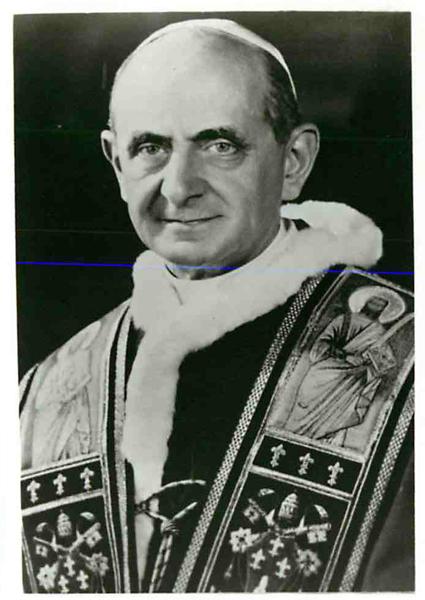

Pope Paul VI was intimately involved in the development of the 1969 Mass. His liturgical training and his experience with the Ambrosian Rite while he was archbishop of Milan made him open to the possibility of using other Eucharistic prayers in addition to the Roman Canon.

On the other hand, he vetoed dropping the prayers during the presentation of gifts. The drafters wanted to deemphasize this part of the rite, which in the past was called the Offertory. There was no question that Pope Paul VI, like Bill Gates, was in charge.

Granted the challenges faced by the reformers, Liturgical Reform 2.0 was an extraordinary achievement. The new lectionary of readings for both Sundays and weekdays provides Catholics with a richer selection of Scripture readings than in the past. The additional Eucharistic prayers, although underutilized by the clergy, are great additions to the prayer life of the church.

People were a bit confused when version 1.0 was rolled out, but they quickly caught on and embraced it and its upgrades. Although a few diehards opposed the reforms, the old version of the liturgy, like DOS, was fading away.

The reforms went a long way toward increasing lay participation in the Eucharist, but the Vatican was hesitant in allowing adaptations of the liturgy to local cultures. The two most significant adaptations were for India at the end of the 1960’s and for Zaire in 1972. They were authorized for experimental purposes for a limited time.

More upgrades were in the making. Additional prayers were written in English for Sunday liturgies that would sync with the liturgical readings of the three-year cycle. Thus, the opening prayer would pick up themes from the readings of each Sunday. A new and better English translation was also prepared by the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL). This 1998 translation was approved by all the English-speaking bishops’ conferences, but never approved by Rome.

Advertisement

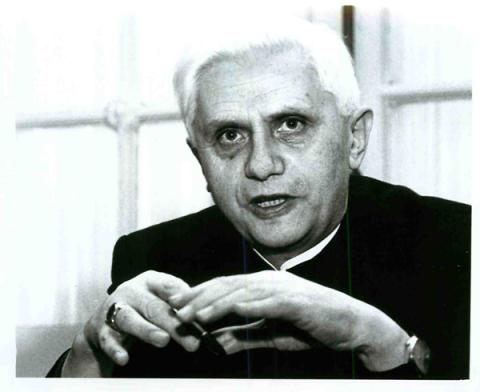

As time went on, the reform movement experienced growing opposition in the Vatican and eventually a hostile takeover by those, including Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who felt the reforms had gone too far. Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, who had spearheaded the reforms, was exiled from Rome and made nuncio to Iran in 1976, where he celebrated Christmas Mass for the hostages in the American embassy. Cardinal Francis George of Chicago in 2002 led a coup at ICEL, removing those who had supported the reform and replacing them with people more in line with Vatican thinking. Rather than respecting local translations, Rome began micromanaging the translations.

Thus, began Liturgical Reform 3.0, or what many called the “Reform of the Reform.” The 1998 ICEL translation was trashed and replaced by an awkward, more literal translation in 2011. It is like MS Vista, a 2007 version of Windows that was rejected by users. Also brought back was the pre-Vatican II Latin version of the Mass. Marketing an old and new version of the Mass has caused confusion among priests and laity. It was as if Microsoft had decided to bring back DOS.

The reform of the reform put a stop to any new innovations. New ideas were unwelcome in Rome.

Pope Paul VI was elected pope in 1963 and served until he died on Aug. 6, 1978, at the age of 80. (Religion News Service file photo)

Early in his papacy, liturgical reform was not a priority for Pope Francis. In 2014, he appointed Cardinal Robert Sarah as prefect of the Vatican Congregation for Divine Worship. The cardinal supports the reform of the reform and has even been promoting Masses where the priest faces east, with his back to the people.

This was perhaps Francis’ worst appointment. Francis had earlier closed down the office Sarah had headed in the Roman Curia and Francis felt he needed to give him a job. The position at the congregation was open.

When the council of cardinals advising the pope asked bishops what issues they thought should be handled by bishops’ conferences rather than the Vatican, the almost universal response was liturgical translations. Bishops were tired of being second guessed by Rome. Cardinal Oswald Gracias of Bombay (Mumbai), India, heard that from every bishops’ conference in Asia.

In response, the pope appointed a commission earlier this year chaired by Archbishop Arthur Roche, the number two man in the Congregation for Divine Worship, to look into the question. This was clearly an end run around the prefect Sarah. The pope accepted their recommendations and Roche explained them to the media.

Church law was clarified by the pope to emphasize the original intention of Vatican II to give primary authority to bishops’ conferences in liturgical translations. The Vatican now simply “confirms” or “ratifies” the approval of the bishops of these translations after reviewing them. No more micromanaging.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the Vatican’s chief theologian under Pope John Paul II, was elected pope in 2005 and served until he resigned in 2013. (RNS file photo by Odette Lupis)

When it comes to “adaptations” or changes in the liturgy, the Vatican’s role is a bit larger. It is to review and evaluate adaptations in order to safeguard the substantial unity of the Roman Rite. What is striking is that the explanatory documents cite Vatican II, which spoke of “radical adaptation” of the liturgy. This appears to be a clear invitation to bishops’ conferences to propose significant changes in the next stage of liturgical renewal.

What might the next stage, Liturgical Reform 4.0, look like.

A first step would be to look at the upgrades that were canceled because of the reform of the reform. Although it would confuse people if their responses at Mass were changed again, it would not cause any problems to let priests use the good 1998 ICEL translation as an alternative to the current bad English translation. Let the users decide which interface they prefer.

A second step is to clarify the position of the pre-Vatican II liturgy. The church has to be clear that this product is being phased out. It is only being allowed out of respect to the sensitivities of the faithful who find change difficult. Baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and ordinations in the old rite should be discontinued. The old rite should not be taught in seminaries. Any seminarian who has problems with the new rite should not be ordained. Parents should be instructed to bring up their children in the new rite.

Third, new prefaces need to be drafted for each Sunday in the three-year cycle that would pick up themes from the Scripture readings of that Sunday so that the congregation would see a connection between the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist.

Fourth, more Eucharistic prayers that include responses from the assembly, as does the “Eucharistic Prayers for Masses with Children II,” are especially needed. The church needs to show that the Eucharistic prayer is not just the prayer of the priest, but of the whole assembly.

A fifth step would examine and experiment with the placement of the kiss of peace, which through the centuries has moved around in the liturgy. The most ancient location was at the end of the Liturgy of the Word.

This last recommendation reminds me to emphasize that the church needs a better process for developing and rolling out changes in the liturgy. The Constitution on the Liturgy speaks of granting bishops’ conferences the power to permit “the necessary preliminary experiments over a determined period of time among certain groups suited for the purpose.”

Rather than having everything coming top down from the Vatican, it is clear that the council fathers expected bishops’ conferences to be creative in developing adaptations. These adaptations, even "radical adaptations," would be tested locally before they were proposed for approval by the Holy See. In the secular world, this is called beta testing or market testing. Getting feedback from the congregation to improve the adaptations would be an essential part of this testing.

Over its 2,000-year history, the Catholic liturgy has constantly changed in response to new situations and cultures. Like software, it must continue to be updated and adjusted to the people and cultures of today. Allowing creativity and experimentation is the best way to prepare for Liturgical Reform 4.0. Pope Francis has opened the door; bishops need to foster creativity.

Pope Francis leads the Chrism Mass in Saint Peter’s Basilica on March 24, 2016. (Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Stefano Rellandini)

[Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese is a columnist for Religion News Service and author of Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.]

Editor's note: Sign up to receive free newsletters , and we will notify you when new columns by Fr. Reese are out.