Evening Mass is celebrated in this file photo taken at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. (Dreamstime/Ruben Gutierrez)

Updated Dec. 6 4:36 p.m. central time: Pope Francis has also joined in the discussion, telling the Italian Catholic television network TV2000 that "lead us not into temptation" is "not a good translation."

"The French have changed the text and their translation says "don't let me fall into temptation," he said in an interview broadcast on the evening of Dec. 6. (here on YouTube in Italian). "It's me who falls. It's not Him who pushes me into temptation, as if I fell. A father doesn't do that. A father helps you to get up right away. The one who leads into temptation is Satan." The original report follows:

PARIS -- It took the French church decades of theological debate, years of waiting and a few days of last-minute controversy to change one phrase in its translation of the classic prayer "Our Father."

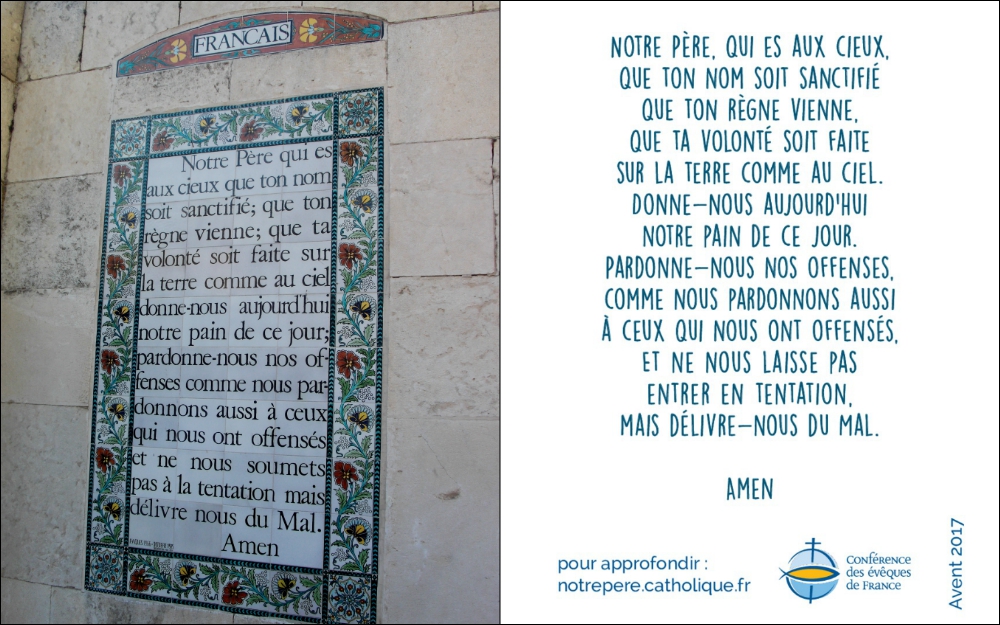

French Catholics finally went ahead with it Dec. 3, the first Sunday of Advent, and Massgoers said, "Let us not enter into temptation," rather than the original wording, "Do not submit us to temptation," chosen after the Second Vatican Council.

In the end, the switch went relatively smoothly, even if some parishioners mumbled the wrong phrase. But it came only after both long discussions about the translation and delays due to the word-for-word wrangling with Rome over other liturgical translations.

As has happened with several other language groups, French bishops are still working on a new translation of the Roman Missal — the book of liturgical prayers that priests use — after Vatican officials said their 2007 translation was not close enough to the Latin original.

Pope Francis' recent loosening of the tight translation guidelines laid down in the 2001 Vatican instruction Liturgiam Authenticam have prompted English- and German-speaking Catholics to consider going back to earlier translations. The issue was never as contentious in French, which is based on Latin, but some changes may be made.

On Sunday, many parishes passed out sheets containing the new French text, with the changed words in bold, to help hesitant parishioners along. At Saint-Ignace, the Jesuit church in Paris, the new wording was written across a large banner for all to see.

Fr. Emmanuel Schwab, pastor of Saint-Léon Parish in Paris, said the new translation was "less ambiguous" than the earlier wording.

"The version 'do not submit us to temptation' made some people think God threw banana peels in front of people to see if they would slip and fall, but that is absolutely not the biblical view of God," he said after Mass.

To English-speaking Catholics, the words of the Lord's Prayer and the Hail Mary were so familiar and uncontested that they survived the post-Vatican II changes intact, including such phrases as "hallowed be thy name" or "blessed art thou among women."

This meant the sixth petition, which followed the Latin text "ne nos inducas" ("lead us not into"), was kept unchanged as well. In other prayers, by contrast, old-fashioned terms were replaced by modern ones, such as Holy "Ghost" giving way to Holy "Spirit."

France's first post-Vatican II Our Father, an ecumenical version agreed with Protestant and Orthodox churches here in 1966, opted to translate the Latin text as "ne nous soumets pas à la tentation." That can be translated into English as "do not submit us" or "do not subject us" to temptation.

Left: The earlier French translation of the Lord's Prayer is seen at the Church of the Pater Noster in Jerusalem (Wikimedia Commons/Laubrière). Right: A brochure from the French bishops' conference gives the new translation.

Other European languages, such as Italian, German and Polish, kept the Latin idea of "lead us not," while the Spanish and Portuguese* translations rendered it more neutrally as "do not let us fall" into temptation.

Critical theologians argued that the new version preserved the notion that God would purposely steer mortals toward sin. This led to decades of debate among experts on what the prayer, which Jesus recited in Aramaic and the evangelists Matthew and Luke recorded in Greek, actually meant.

In the 1970s, ecumenical liturgists from around the English-speaking world produced a dynamic translation — "save us from the time of trial" — that was meant to reflect the sense of the petition rather than its literal wording.

The idea of "trial" rather than "temptation" came from the original Greek of the Gospels, which used the term peirasmos (πειρασμόσ). It can mean "trial" or "testing" or, as St. Jerome chose when translating the Bible into Latin, "temptation."

Some French theologians are still unhappy with the new wording because it retains the idea of "temptation" rather than "trial." But they see little chance of a further change, especially since the Vatican approved the new Our Father four years ago when it gave the green light to a new liturgical translation of the Bible.

The delay in introducing the new wording came because the bishops were waiting for the retranslation of the Roman Missal that Rome demanded, which was expected to be ready at the start of Lent in 2017.

The stricter norms were also causing problems elsewhere. When the new English translation was introduced in 2011, many priests complained the prayers sounded stilted and unnatural.

After Rome rejected German bishops' new translation in 2013, they disagreed on several points and seem to have dropped their retranslation efforts altogether in October after Francis issued the document Magnum Principium, which gives responsibility for translations back to local bishops' conferences.

Bishop Guy de Kerimel of Grenoble, France (Wikimedia Commons/Paralacre)

Impatient with the delays in the French translation of the missal, bishops in Belgium and Benin introduced the new Our Father wording at Pentecost this year. French speakers in Switzerland will start using it next Easter while Quebec will wait until Advent 2018.

Bishop Guy de Kerimel of Grenoble, who heads the French episcopal liturgy committee, said last month that Magnum Principium would have a limited effect on the next French version of the Roman Missal, which missed its announced publication date this year.

"There's a natural tendency to start all over again from scratch, but most bishops don't want to do that. A lot of work has already been done," he told the Catholic television network KTO during the bishops' fall plenary session in Lourdes.

"The motu proprio means that we'll have to reread the translation and maybe tidy it up a bit. We hope to present it to Rome during the year 2018, which means there will be a new edition of the missal in 2019," he said.

The bishop did not say what he thought might be changed. In a separate interview, he told the Catholic daily La Croix that the texts for confirmation and the Liturgy of the Hours still needed to be retranslated.

The new translation is meant for use in all French-speaking countries and regions — France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Canada, Haiti, West Africa and North Africa — and local variations in usage can lead to unexpected problems.

For example, Rome rejected the word coupe ("cup") for the Latin calix and insisted the new edition use the word calice ("chalice"). But the translators wanted to avoid that because calice is also a swear word in Québécois French. The Vatican traditionalists insisted they were right, but this looks likely to be changed under Francis' rules.

The new translation also includes "consubstantial" in the creed, the same as in English, rather than "of the same nature" contained in the earlier French version. But this sounds less stilted in French and goes back to the pre-Vatican II wording, so its reintroduction was less noticed.

Advertisement

The change in the Our Father was reported in the secular media here and even prompted an intellectual dispute. Unlike other Left Bank-style debates, though, this one ended with a confession.

A week before the change, philosopher Raphaël Enthoven argued in his short morning commentary on Europe 1 radio that the new wording contained a subliminal Islamophobic message because it dropped the idea of "submission" from the Our Father.

"The problem is not temptation, it's that they dropped the verb soumettre and thus removed from the text the idea of submission," Enthoven said, noting the French knew "Islam" literally means "submission" (to God) long before author Michel Houellebecq wrote his controversial novel Submission about a future Muslim takeover of France. The book was published in January 2015 on the same day as radical Islamists killed 12 people at the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, which regularly mocked Islam.

According to Enthoven, the change to the Our Father translation gave the prayer a hidden message, that "God does not submit us to anything, we are not Muslims, we believe freely."

Church spokesman Msgr. Olivier Ribadeau Dumas promptly tweeted: "This is simply sad and ridiculous."

The Muslim website SaphirNews called his argument "a grotesque shortcut."

Two days later, Enthoven said he had received "hundreds, thousands of comments" via social media that slowly convinced him "that I've said something stupid."

In a long interview that sounded penitential, he told La Croix that he had wrongly read the translation as a reflection of France's concerns about Islam.

His change of heart was well-received. Catholic blogger Fr. Pierre-Hervé Grosjean thanked him for his public apology. "My next Our Father will be for you ;) ," he tweeted.

[Tom Heneghan is Paris correspondent for the London-based weekly Catholic magazine The Tablet.]

*Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Portuguese use "lead us not" in their translation of The Our Father. The Portuguese, in fact, use the phrase "do not let us fall" into temptation.