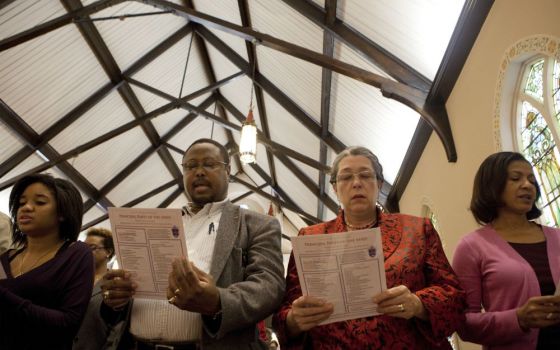

Catholics at the Shrine of the Sacred Heart in Washington, D.C., attend Mass for the feast of the Assumption Aug. 15. (CNS/Rhina Guidos)

Pope Francis' letter to Cardinal Robert Sarah, correcting him on the procedures now in force for producing liturgical translations, has been both praised and denounced as an ecclesiastical "slap down." The publication of this letter, however, is an occasion for neither right-wing handwringing nor left-wing schadenfreude.

This is not about ecclesiastical one-upmanship. It is simply one more example of Francis' consistent determination to implement the vision of the Second Vatican Council. If his actions continue to surprise us, it is because, five decades out, there remains a substantial gap between the council's reformist agenda and its concrete realization in the life of the church. Let's begin with a little background.

This imbroglio has its remote origins in the momentous decision of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) to give regional episcopal conferences, sometimes singly and sometimes banding together, primary responsibility for producing vernacular translations of liturgical texts. This was the common practice for more than three decades.

However, in 2001, the Vatican's Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments issued Liturgiam Authenticam, a document that shifted much of the responsibility for these translations away from episcopal conferences and back to the Vatican.

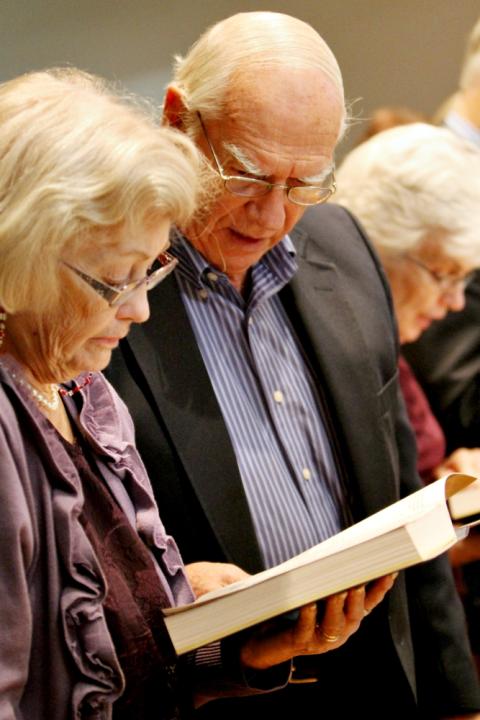

Parishioners read the profession of faith during Mass at St. John Nepomucene Church in Bohemia, New York, on the first Sunday of Advent in 2011, the first time the new English version of the Roman Missal was used throughout the U.S. (CNS/Long Island Catholic/Gregory A. Shemitz)

The revised translation process included a line-by-line Vatican assessment of all liturgical translations, often resulting in the imposition of thousands of amendments to the submitted translation. Liturgiam Authenticam also called for a much stricter "fidelity" to the original Latin text.

Unfortunately, the price of this stricter fidelity was often a diminishment in the texts' intelligibility and "prayability." In the English-speaking world, this problematic new procedure yielded the much-criticized 2011 English edition of the Roman Missal.

Enter Pope Francis. In September, he issued Magnum Principium, a document that revised canon law by returning authority for liturgical translations back to the episcopal conferences. It also revised some of the norms for liturgical translation that had been established in the 2001 document. Francis expanded the earlier document's insistence on "liturgical fidelity" to include not only fidelity to the Latin text but also fidelity to the language in which the text would be translated and fidelity to the comprehension of the worshiping community.

Soon after the publication of the papal document, Sarah, prefect of the Vatican's worship congregation, wrote a commentary that appeared to minimize the changes the pope had called for. The commentary insisted on the continued authority of Liturgiam Authenticam and it held that the pope's revised process for producing liturgical translations left in place the rigorous Vatican examination and correction of proposed liturgical translations.

It was at this point that Francis took the surprising step of issuing a public letter to correct Sarah's interpretation of Magnum Principium. The pope insisted that he had, in fact, revised some of the translation norms established by the 2001 document. Moreover, he asserted that Magnum Principium does in fact call for a much-reduced Vatican oversight of the translation process. For example, the worship congregation was not, as Sarah had suggested, still authorized to impose extensive translation changes on episcopal conferences. Finally, the pope instructed Sarah to send his letter to every media outlet in which Sarah's commentary had appeared.

Advertisement

So, what are we to make of all of this? In my view, the pope's letter to Sarah is not about evening scores with ideological enemies. Rather, it is but another concrete confirmation of the pope's single-minded intention to realize the council's reformist agenda. He may be the first post-conciliar pope not to have played a role at Vatican II, but no pope has more comprehensively summoned forth the council's comprehensive call for reform and renewal. His letter to Sarah reinforces this in several ways.

First, his response to the African cardinal indicates his robust commitment to one of the animating principles underlying the council's reform of the liturgy. In the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, the council taught that an authentic liturgical renewal should enable "the full, conscious, and active part in liturgical celebrations which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy" (14).

Such a renewal would ensure that "the Christian people, as far as is possible, should be able to understand them [various liturgical texts and rites] easily and take part in a celebration which is full, active and the community's own" (21).

Cardinal Giovanni Montini (the future Pope Paul VI), cleverly adapting Jesus' famous teaching on Sabbath observance, pithily captured the council's intent — the liturgy was made for men and women, not men and women for the liturgy. This principle clearly guided Francis' call for a liturgical "fidelity" attentive to both the language in which a text is being translated and the enhanced comprehension of the people.

Second, the letter attends to one of the council's most significant contributions: its re-discovery of a theology of the local church and the value of local customs and cultures. In the liturgy constitution, the bishops broke free from a stifling liturgical uniformity to rediscover the church's catholicity, a Spirit-animated unity-in-diversity. The liturgy was not celebrated on some ethereal plane but in a concrete place and time and with a specific people.

Pope Francis celebrates Mass Sept. 18 in the chapel of Casa Santa Marta at the Vatican. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

According to the council, the church should cultivate and foster "the qualities and talents of the various races and nations" (Sacrosanctum Concilium 37). Local churches, the council encouraged, should be willing to "borrow from the customs, traditions, wisdom, teaching, arts and sciences of their people" (Ad Gentes 22). This could include the incorporation into the liturgy itself, when possible, of certain elements drawn from local cultures.

Obviously, if one's goal is to produce liturgical translations sensitive to local cultures, including the distinctive nuances embedded in the languages of peoples, it is the local church that is best equipped to oversee those translations. By "local church" here, I do not mean only the local diocese (which Vatican II at times referred to as a "particular church") but the churches of a particular region. This is why the council originally handed over to episcopal conferences the responsibility for liturgical translations (Sacrosanctum Concilium 22, 36, 40, 63) and it is why Francis, in both Magnum Principium and his letter to Sarah, reestablished the council's intention.

Third, the pope's return of liturgical authority to episcopal conferences also reflects his commitment to the council's teaching on episcopal collegiality. Vatican II taught that the bishops shared with the pope "supreme and full authority" in pastoral service of the universal church (Lumen Gentium 22).

Unfortunately, the council was unable to give this important principle robust institutional form; its transfer of authority over liturgical translations to episcopal conferences represented an important exception.

It should not surprise us that Francis would use his papal authority to return to episcopal conferences the authority that Liturgiam Authenticam had largely taken from them. He has made the fortification of robust collegial structures — whether episcopal conferences, the documents of which he cites with unprecedented frequency, or the world Synod of Bishops — a central feature of his pontificate.

Fourth, at Vatican II, the bishops had pleaded for a reorganization of the Roman Curia "in a manner more appropriate to the needs of our time" (Christus Dominus 9). This simple statement distilled the many complaints echoed in the council hall regarding curial officials' abuse of their office.

His letter to Sarah reminds us that Francis is again heeding the council's call. As is well-known, this Argentine pope has made curial reform a central feature of his pontificate. Unfortunately, the success of this reform has been uneven to date, in no small part due to ecclesiastical intransigence by many curial officials.

Francis has been more successful in redirecting the flows of ecclesial power away from Vatican congregations and toward more collegial structures. We have seen this in the prominent role given to the Synod of Bishops. He has invited synodal assemblies, episcopal conferences and special commissions to address pressing questions that his predecessors would have likely remanded to one or another of the Vatican dicasteries (e.g., pastoral care of those in "irregular" marriages; the possibility of women deacons).

Cardinal Robert Sarah (Wikimedia Commons/François-Régis Salefran)

Obviously, this was one of the principal objectives of Magnum Principium, but it is also evident in Francis' public letter to Sarah. The Curia is not to impose itself unduly on work that can better be achieved through other more collegial and subsidiary structures.

Some have wondered why the pope moved so quickly and publicly to respond to Sarah while refusing to respond either to the now infamous dubia published by four cardinals, or the more recent "filial correction" of presumed doctrinal errors. The answer was simple. The latter two cases represent criticism of the pope's theological commitments and his interpretation of church teaching. The pope has shown himself to be remarkably tolerant of such criticism.

In the case of Sarah, however, we have a member of the Curia charged by virtue of his curial office with executing the pope's pastoral agenda. Publicly contravening that agenda through a blatant misinterpretation of a key papal document represents not merely an unseemly breach of ecclesiastical etiquette; it constitutes a failure to properly fulfill the demands of his office and, as such, had to be corrected.

We are over four and half years into this pontificate and yet this pope can still surprise us. He surprises us by his refreshing return to the simplicity and joy of the Gospel and he surprises us by his conviction that St. John Paul II was right: Vatican II is "a sure compass," guiding our church on the path of reform and renewal.

[Richard R. Gaillardetz is the Joseph Professor of Catholic Systematic Theology at Boston College. He is the author of An Unfinished Council: Vatican II, Pope Francis, and the Renewal of Catholicism (Liturgical Press, 2016).]