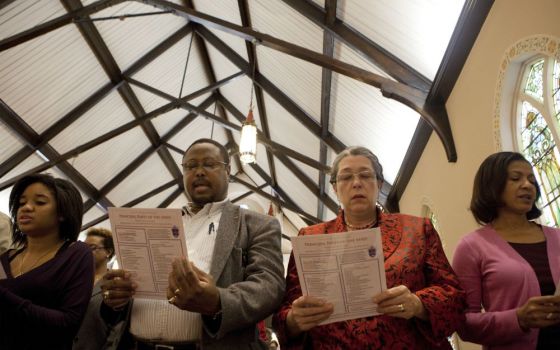

Parishioners use Mass guides during a Sunday morning service at St. Joseph's Catholic Church in Alexandria, Virginia, Nov. 27, 2011. The new English translation of the Roman Missal was used for the first time in churches across the nation on the first Sunday of Advent. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Eminent Jesuit theologian Fr. Gerald O'Collins has appealed to every English-speaking episcopal conference in the church to seize the moment, dust off the 1998 English translation of the Roman Missal and substitute it for the contentious and clunky 2010 translation. In his new book, Lost in Translation: the English Language and the Catholic Mass, O'Collins, who is currently a research professor at the Jesuit Theological College in Australia, scrutinizes the church's "liturgy wars" and the Vatican's "usurpation" of the local bishops' authority.

With coauthor John Wilkins, former editor of London's The Tablet, O'Collins writes that the Second Vatican Council gave bishops' conferences the responsibility of translating liturgical texts, but that the 2001 Vatican instruction Liturgiam Authenticam took that duty away from the bishops and gave it the Congregation for Divine Worship.

The 1998 translation of prayers Catholics use in liturgy, which O'Collins terms as "the missal that wasn't," failed to obtain the Congregation for Divine Worship's imprimatur and was ultimately replaced by a revised translation in 2010, which was introduced into parishes in November 2011.

The Vatican Congregation also replaced the International Commission on English in the Liturgy, which had translated the prayers from the original Latin, with the Vatican-controlled Vox Clara ("clear voice") commission under the presidency of Australian Cardinal George Pell.

This saw the emphasis in translation shift from "dynamic equivalence" to a more literal translation of the Latin, or what Maxwell E. Johnson of the University of Notre Dame has termed "impossible syntax and forced 'sacral language.' "

Lost in Translation was published just as Pope Francis issued new instructions on his own initiative in September, the document Magnum Principium, which reevaluates Liturgiam Authenticam and returns the duty of translation to local bishops' conferences.

A 'scandalous takeover'

In the book, the authors argue that the imposition of the 2010 translation was the outcome of a "scandalous takeover" by conservative elements in the Vatican, and O'Collins urges bishops' conferences to seize this moment to roll back on that turn of events.

Wilkins outlines the maneuverings that dismantled the International Commission on English in the Liturgy and how Cardinal Medina Estévez, the prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, swept aside the international commission's 16 years of work, even though its translation of the missal had been approved by all 11 of the English-speaking conferences of bishops participating.

John Wilkins

In an interview with NCR, John Wilkins explained that his research for his chapter in the book is based on "access to all the essential sources — not just people but also documents."

Paying tribute to O'Collins' "extremely impressive scholarship" and his "stringent comparison" of the two translations, Wilkins said it shows how the 2010 missal translation fails to advance what the Second Vatican Council mandated, namely the full participation of priest and people. O'Collins also critiques the unsatisfactory principles prescribed by Liturgiam Authenticam.

The book's purpose, O'Collins writes, is to show how far superior the 1998 translation is to that of the 2010 missal.

"I have written out of a desire that the English-speaking conferences of bishops will act quickly and, by introducing the 1998 Missal, allow the presiders and congregations to celebrate the liturgy in what is truly their own language," O'Collins states.

He is highly critical of the 2010 missal's "quest for a mythical 'sacred vernacular' " that favors "odd, 'stately' words, obsequious ways of addressing God, and a non-inclusive language that leaves out half the human race."

Advertisement

Wilkins concurs. He told NCR, " 'For us men and for our salvation' in the Creed — propter nos homines — isn't even a correct translation because the Latin homo doesn't mean 'man' as opposed to 'woman' — that is vir. I find it difficult to say those words. You simply can't do it — but they do!"

O'Collins also argues that the literalist, word-for-word 2010 translation is hard to proclaim, not least because of its long, Latin sentences that do not fit the English language.

"This sacred vernacular with which the English-speaking churches were saddled in Advent 2011 asks me to prefer 'charity' over 'love,' 'compunction' over 'repentance,' 'laud' over 'praise,' 'supplication' over 'prayer' and 'wondrous' over 'wonderful,' " he complains.

He adds that the missal "calls on me persistently to use a language of 'merit,' which moves close to the ancient heresy derived from Pelagius. Pelagius held that through our own efforts we can gain salvation. I find it distressing to read texts that encourage a do-it-yourself redemption."

Another concern the book highlights is the 2010 missal's lack of ecumenical sensibility. According to Wilkins, "There was enormous sadness expressed in ecumenical circles" over this because ecumenical dialogue had brought about agreed texts for the Sanctus, the Creed and the Gloria. Now these were abandoned. When Horace Allen, a Presbyterian liturgist and professor emeritus of worship at Boston University read Liturgiam Authenticam, he stated, "Something terrible has happened which I could never have imagined — a trusted and beloved ecumenical partner had just walked away."

In his analysis, O'Collins examines the possible reasons for the sidelining of the 1998 missal, asking if it were due to an ongoing failure to honor the collegiality taught by the Second Vatican Council, was it "a failure that allowed centralized, largely unaccountable authorities and the idiosyncratic views of a powerful few to prevail?"

Return to collegiality

In the late 1990s, real collegiality, especially in the functioning of bishops' conferences, suffered a wintry season, O'Collins notes:

"Cardinal Medina's anti-collegial 'no' to a missal approved by the episcopal conferences of the English-speaking world coincided with a 1998 motu proprio of John Paul II, Ad Apostolos Suos, which required unanimous decisions when bishops' conferences were voting on doctrinal matters. Where such unanimity is not achieved, the teaching must be referred to the Holy See for its approval or disapproval. This effectively emasculated doctrinal teaching coming from such conferences by requiring from them a higher standard than that which prevailed at Vatican II."

"Pope Francis made it clear that it was the bishops, as per Vatican II's instruction, and as taken away by Liturgiam Authenticam, who will oversee the translations and approve them. That is putting it back into the bishops' court."

- John Wilkins

Though Wilkins believes that pressure from the laity will be crucial in bringing about change, he believes spearheading change must come ultimately from the bishops' conferences, and he is hopeful in view of some bishops' outspokenness on this issue. In a statement issued Oct. 26, the New Zealand bishops' conference voiced support and thanks for Pope Francis's Magnum Principium, which they described as a "bold directive."

Admitting their frustration with some aspects of the current translation of the Roman Missal, they said they would "seek to explore prudently and patiently the possibility of an alternative translation of the Roman Missal and the review of other liturgical texts."

In the same month, the German bishops appeared to signal their abandonment of a new translation of the missal based on Liturgiam Authenticam, which Cardinal Reinhard Marx described as "a dead end."

Closer to home, Wilkins believes the English-speaking bishops in England and Wales feel over-weighted by the American hierarchy, with its superior number of bishops. "The question is: How do we get them [English and Welsh bishops] to move?" Wilkins asks. "I think it is so important that the laity write letters to their bishops and speak up. The whole thing is ready, and we could move now."

Wilkins is realistic about the challenges that his and O'Collins' call on the 1998 missal faces, as the clerical culture in the church means bishops find it hard to admit that they have been wrong. That is why the laity will be crucial to change.

But the most hopeful sign is Pope Francis himself.

"We couldn't have guessed when we started work on the book that by the end of 2017 the field would be completely changed by Pope Francis' motu proprio Magnum Principium, in which he has made it quite clear that he meant what he said about a review of Liturgiam Authenticam being necessary," Wilkins said. "Not only that, but he made it clear that it was the bishops, as per Vatican II's instruction, and as taken away by Liturgiam Authenticam, who will oversee the translations and approve them. That is putting it back into the bishops' court."

Francis, Wilkins emphasizes, is "a Vatican II person — he believes in collegiality and the governance of the church by the pope and the bishops, not by the pope and the Roman Curia. The way the Vatican took away the bishops' prerogative given to them by Vatican II is something that has stuck in his throat."

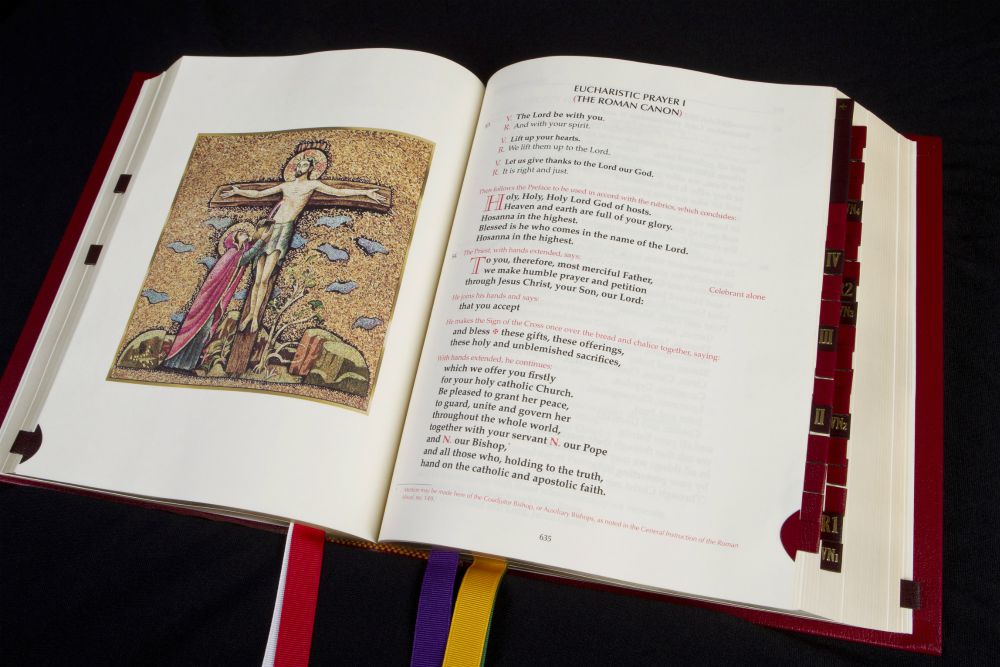

The first eucharistic prayer is seen on a page from a copy of the new Roman Missal in English published by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

The sorry tale of the 1998 "missal that wasn't" was, he believes, "a power grab" linked to the change of climate in Rome that John Paul II's pontificate heralded, promoting centralization of authority over collegiality. "It was a grab for control. In contrast, Pope Francis thinks of the church as unity in diversity and diversity in unity — he sees the value of all the local churches."

According to Wilkins, bishops acknowledge privately that the translation is not good. "If you are offering thanks to God, you can't offer second best — 2010 is second best. There is a pent up feeling amongst many bishops and even cardinals who have got to defend this translation." But he warns that inertia could be a hindrance as well as logistical considerations like the cost of producing, printing and distributing a new missal.

Wilkins believes the translations should be on the agenda of every bishops' conference and that bishops' conferences need to grasp the implications of Francis' recent initiatives. The New Zealand bishops appear to have already done so with their October statement, noting that the pope had "reaffirmed the teaching of the Second Vatican Council which states that it is local groupings of bishops who oversee then approve translations into the language of the land, before seeking final acceptance of this work by the Holy See."

Wilkins told NCR, "The road is open now, so we have got to give it a push because people have given up. But after what has happened this this year through Pope Francis, the impossible has become possible."

In the book, O'Collins argues that there is no need for the new commission set up by Francis to review Liturgiam Authenticam to concern itself with whether or not there should be another translation of the Roman Missal.

"It does not need to. Waiting in the wings is a translation, prepared by the original [International Commission on English in the Liturgy] and approved by all the English-speaking bishops' conferences. Take it down from a Vatican shelf, dust it off, and make a few additions. Then Mass in the vernacular can become, as it should be, a powerful tool of evangelization when people experience it."

[Sarah Mac Donald is a freelance journalist based in Dublin, Ireland.]